Why is it that the final poem of the book you’re working on, the one that ties the entire volume together, always proves to be the most difficult to revise?

Why is it that the final poem of the book you’re working on, the one that ties the entire volume together, always proves to be the most difficult to revise?

Fabulous Beast, by Sarah Kain Gutowski: Fabulous Beast is divided into three sections—“The Sow,” “The Woman With The Frog Tongue,” and “Minor Gods”—that are bookended by a prologue and epilogue. The prologue and epilogue frame the book as an exchange between mother and daughter in which, broadly speaking, the three inner sections are stories the mother tells to explain things to her daughter about what it means to be a woman and a mother in a world where very specific and idealized versions motherhood and womanhood might be valued, but actual women and mothers are systematically devalued and dehumanized. That programmatic and overtly political nature of that description, however, does not do the book justice. This is a book of poetry, not a polemic. Gutowski’s concern—animated without question by a feminist perspective—is less about, for example, making women’s oppression per se visible than it is about capturing, with all its internal contradictions and ironies, the interior experience of trying to build a meaningful life as a woman and/or a mother under the terms that oppression imposes. She does this by weaving the women she writes about into narratives built from elements of fairy tale, myth, and even horror. Neither the sow, nor the woman with the frog tongue, nor the woman who appears in “Minor Gods,” in other words, is a crusader in any obvious sense of that term; and much of the book’s power derives from the fact that none of the sections—each of which deserves a review on its own terms—resolves in an obvious, polemical manner. I think it would be very interesting to read Fabulous Beast next to Julia Kolchinsky Dashach’s 40 Weeks, which is also about motherhood and which I wrote about in Four by Four #17, and I found it really interesting that Gutowski’s “Mama, Couldn’t She Eat a Fly? Because She Has a Frog Tongue,” in which the woman with the frog tongue has a dream about her arm detaching itself from her body, immediately recalled for me the protagonist of Moon Brow, by Shahriar Mandanipour (translated by Sara Khalili), who spends the entire novel searching for the arm he lost in Iran’s war with Iraq. I have not thought deeply about this connection, but it might be something worth pursuing. The last thing I will say about Fabulous Beast is how much I admire how well-crafted the poems are. In her notes Gutowski says that the form of “The Woman With The Frog Tongue” is based on Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie Queen,” and what she does with the form is really interesting, but you can tell that Gutowski paid the same careful attention to form in the other two sections as well. The language of these poems is orchestrated, in every sense of that term, and they bear study on that level.

§§§

William Labov, Who Studied How Society Shapes Language, Dies at 97, by Clay Risen:

In one famous study, he went to three department stores in New York City — high-end Saks Fifth Avenue, middle-class Macy’s and budget-level S. Klein — and asked for an item he knew was on the third or fourth floor. What he found confirmed his hypothesis that the New York accent was shaped not just by region but by class: The more expensive the store, the more likely he was to hear the “r’s” in “fourth floor.” What was more, he recognized that the salespeople he asked at Saks were unlikely to be upper class themselves — instead, he concluded, they code-switched to a type of speech that fit their customers.

I studied Labov’s work when I was a graduate student in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at Stony Brook University. I remember well our discussion of this study’s relevance to what it means for an adult English-language learner to try to make sense of the different registers of the language they would be likely to encounter in their daily lives. The truly eye-opening aspect of Labov’s work, however, at least to me, was his study of what was then called Black English, but has since been called by a range of names, including African American Vernacular English and Ebonics. The book he wrote is called “Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular.” I don’t remember if we read the entire book, but I was deeply moved by the way his study exposed the racism inherent in the promotion of the variety of English I spoke as not just the only correct way to speak, but also the only one that could truly be called a language. He distilled much of what he had to say in that book for a popular audience in a 1972 article he wrote for The Atlantic called “Academic Ignorance and Black Intelligence.” I started using this article to introduce the grammar class I taught because I was surprised by how many students who registered for the class held some (admittedly watered-down ) version of the beliefs about African American Vernacular English (AAVE) that Labov was fighting against:

The most extreme view which proceeds from [the deficit model of understanding AAVE]—and one that is now being widely accepted—is that lower-class black children have no language at all. Some educational psychologists first draw from the writings of the British social psychologist Basil Bernstein the idea that “much of lower-class language consists of a kind of incidental ‘emotional accompaniment’ to action here and now.” Bernstein’s views are filtered through a strong bias against all forms of working-class behavior, so that he sees middle-class language as superior in every respect–as “more abstract, and necessarily somewhat more flexible, detailed and subtle.” One can proceed through a range of such views until one comes to the practical program of Carl Bereiter, Siegfried Engelmann, and their associates. Bereiter’s program for an academically oriented preschool is based upon the premise that black children must have a language which they can learn, and their empirical findings that these children come to school without such a language.

This article is still worth reading today, as is the obituary I linked to initially.

§§§

Boneyarn, by David Mills: The subject of this collection is the Negro Burial Ground in what is now Lower Manhattan: the land itself; the people buried there; the politics, of slavery and otherwise, that led to the founding of the cemetery; and more. I think I might have known the Burial Ground existed before I read this book, but I had no idea just how disturbing and complex the history behind it is, ignorant as I am about the legacy of slavery here New York City, where we like to think of ourselves as always having been “above such things.” Indeed, each time I referred to the notes Mills provides, I found myself wishing that Ashland Poetry Press had published the poems as part of a two-volume set, with the other volume containing the history that Mills has to fill in so that a reader will have better access to the many-layered richness he’s packed into the poems themselves. You don’t necessarily need the history to appreciate the poems, but since part of the purpose of this book is clearly to educate, it would have been interesting to see how knowing a fuller historical context would have changed the way the poems “hit.” The strongest poems in the book break down into two categories: those like “Chimney Sweep Apprentice” or “Coating: Warwick” in which Mills inhabits the voices of the people he learned about through his research and those like the ones titled “Talking To The Bones,” in which he imagines himself into the allusive, enigmatic, and epigrammatic, voices of the bones of the dead. Throughout the book, I enjoyed watching Mills’ work through the challenge of finding the forms—poetic, syntactic, rhythmic—that would hold this history that so few people know about, and I would remiss if I did not note, as I did talking about Fabulous Beast above, the pleasure I often took in letting the finely tuned music of Mills’ poetry wash over me. Finally, the section titled “Jupiter & Wheatley’s Suite,” sent me back to an essay I had not read in several decades, June Jordan’s “[The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America”][ Something like a sonnet for Phillis Wheatley](https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/68628/the-difficult-miracle-of-black-poetry-in-america).” It’s an essay worth reading next to David Mills’ book.

§§§

Things Not Seen, by Hrag Vartanian and Valentina Di Liscia:

A wave of anti-Palestinian repression has swept the Western art world in the aftermath of October 7th, 2023. From Amsterdam to San Francisco, artists who have criticized Israel’s brutal war on Gaza have seen their exhibitions canceled, their work deinstalled, and other opportunities rescinded.”

This article catalogues thirteen pieces of art that were, in the words of the authors, “either targeted by cultural entities or removed in protest” because of the artists’ stance regarding Israel and Palestine. I don’t have the rights to reproduce any of that art work in the “Four Things To See” section below, but reading the article reminded me of “Sun City,” a protest song from the anti-apartheid movement in the United States produced in the 1980s by Artists United Against Apartheid. I’ve included a YouTube video in the “Four Things To Listen To” section.

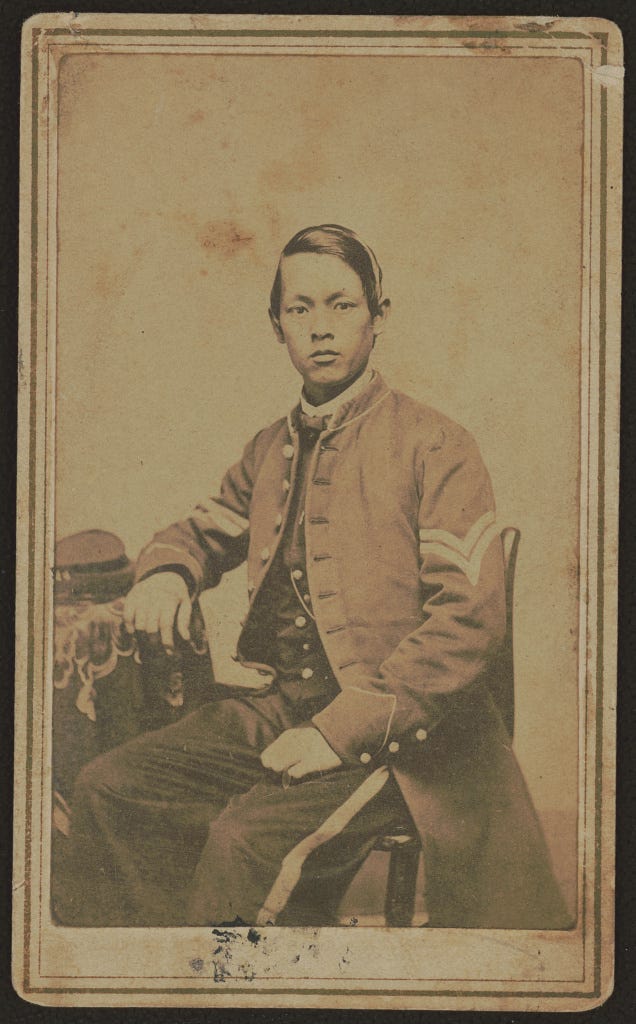

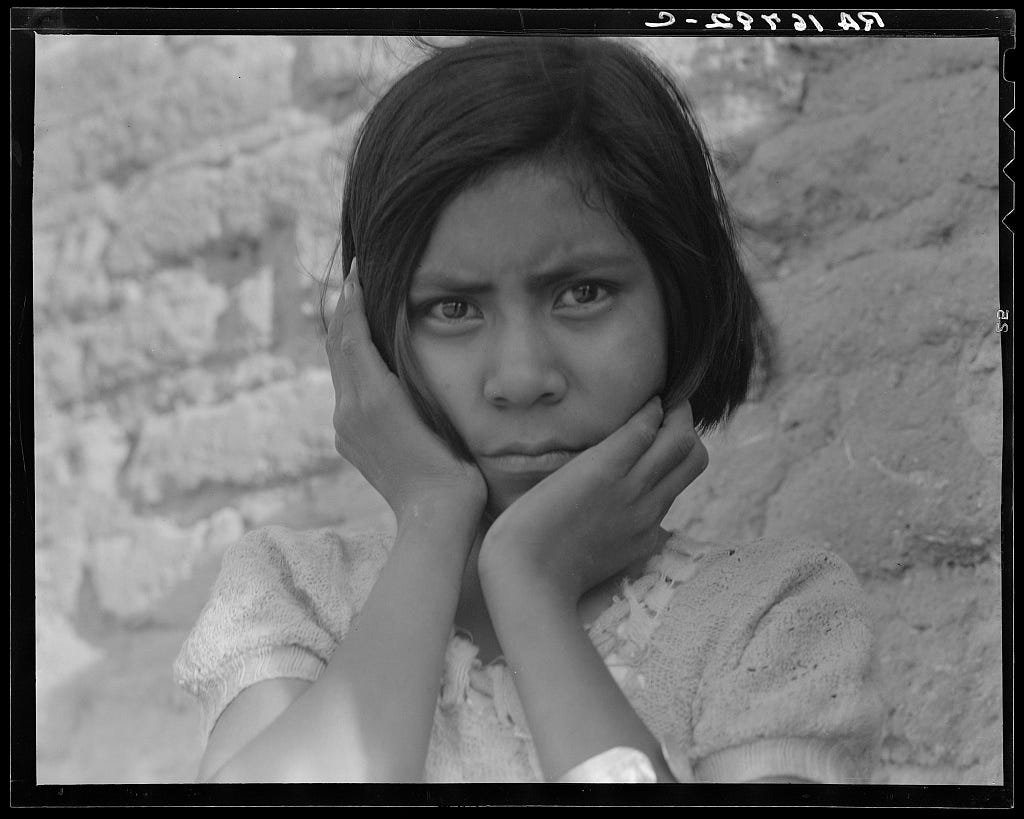

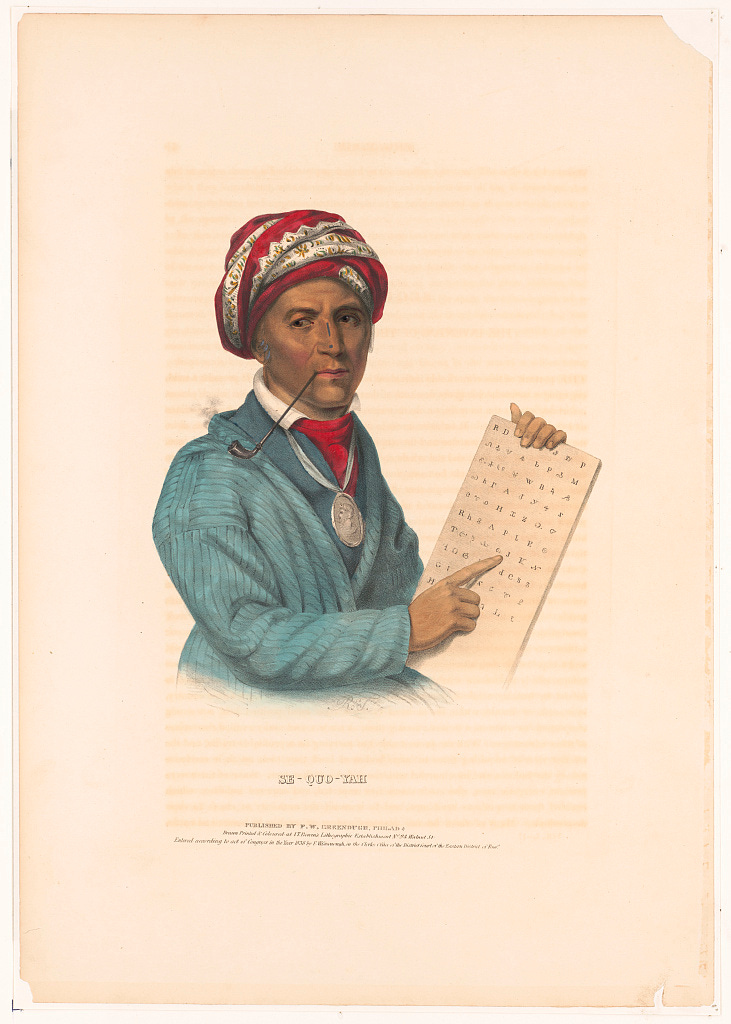

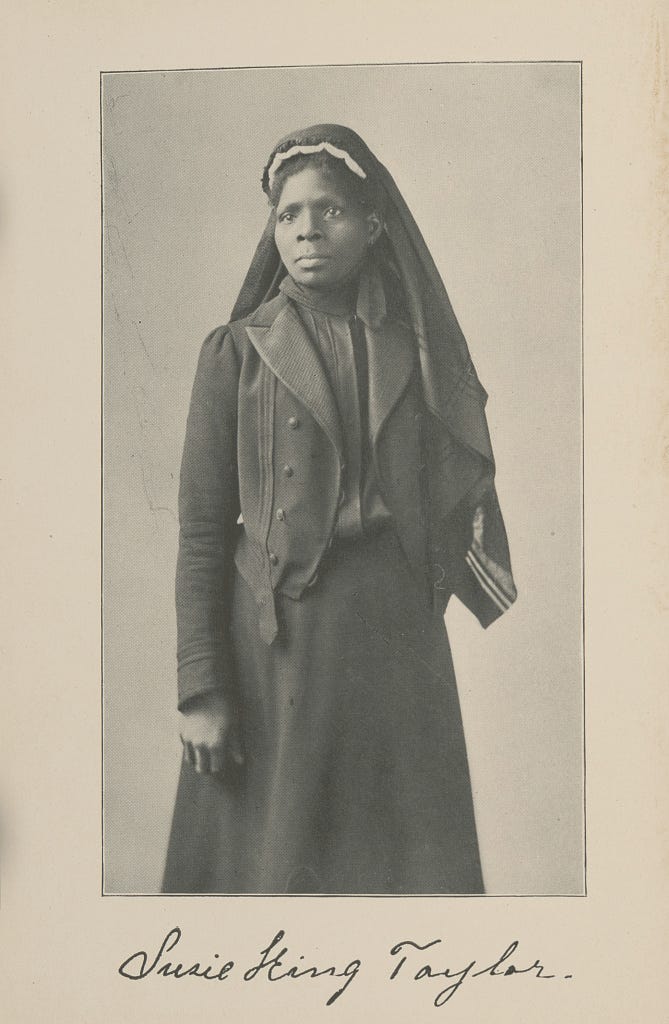

These images are all from the Library of Congress and are all in the public domain.

Corporal Joseph Pierce of Co. F, 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment achieved the highest rank for a Chinese American soldier during the Civil War. (Photo by William Hunt, 1862-1865)

§§§

Photograph by Dorothea Lange, May 1937

§§§

Portriat print by John T. Bowen, 1838

§§§

Susie King Taylor served more than three years as nurse with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War, although officially enrolled as a laundress. She also taught children and adults to read while serving with the regiment.

This is from Wikipedia: Steven van Zandt, upset by the fact that artists from Europe and North America were willing to perform in Sun City, a whites-only luxury resort in the “homeland” of Bophutatswana, persuaded artists including Bono, Bruce Springsteen, and Miles Davis, to come together to record the single “Sun City,” which was released in 1985. The single achieved its aim of stigmatizing the resort. The album was described as the “most political of all of the charity rock albums of the 1980s.” “Sun City” was explicitly critical of the foreign policy of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, stating that he had failed to take firm action against apartheid. As a result, only about half of American radio stations played “Sun City.” Meanwhile, “Sun City” was a major success in countries where there was little or no radio station resistance to the record or its messages, reaching No. 4 in Australia, No. 10 in Canada and No. 21 in the UK.

§§§

§§§

§§§

When I switched from public school to yeshiva after seventh grade, I was one of the top students in my class. I don’t remember if I had the highest grades, but I am pretty sure I was in the top five percent, if not higher. As I recall, I did not want to switch schools, but someone—I don’t think I ever knew who—offered me a full scholarship based on how fully I embraced what I was learning about being Jewish in the after-school Talmud Torah I’d been attending and on my stated desire at the time to be orthodox when I grew up. (My family was not observant.) My mother and my grandparents thought it would be foolish to turn the offer down, though their reasoning had nothing to do with religion. They were convinced I would get a better education in the yeshiva than I would in public school. In some ways, they may have been right. The experience of “learning Torah” trained me in a kind of critical thinking that I don’t think would have been back then part of a high school public education, but an equally important lesson, one that I have carried with me ever since, is just how corrosive an overemphasis on getting good grades—which there meant getting straight A’s—could be. It wasn’t that I thought doing well was unimportant, but watching how unhappy my top-of-the-class classmates were as they stressed over whether or not they would ace their entire report card—to win their parents’ approval, to get into the college they wanted to go to, or some combination of both—helped me begin to understand that getting a good grade was not necessarily the same thing as truly learning something. That distinction remains to this day a central part of my pedagogy.

§§§

We graduated from the yeshiva with our high school diplomas in 11th grade. We could choose from three options for how to spend the following year. You could go to Israel to learn Torah in a yeshiva; you could attend a special program in which you learned Torah in the morning and took college classes in the afternoon; or you could go back to public school for 12th grade. I opted for the third choice, but I was completely unprepared for how I was received by the people who had been my classmates in sixth and seventh grade. Some of them, for example, would not talk to me until they found out that my class ranking was lower than theirs. One episode remains firmly fixed in my memory. A girl named Debbie, along with whom I had been one of the top two students in sixth grade, asked to see my schedule. Since I had already fulfilled all my graduation requirements, I had been enrolled in only one AP class, English, and the rest of my schedule was filled out with electives. Debbie—who, like all the students at the top of our class, was enrolled in all the AP classes that were available to her—tossed my schedule dismissively back onto my desk. “What did they teach you at that fancy, private school? To be lazy?” I don’t think she said two words to me for the entire rest of the year.

§§§

I started losing my hair when I was around fifteen years old, which meant that, by the time I reached 12th grade, I looked older, sometimes a lot older, than my classmates. This, coupled with the fact that I had come back to the school as a senior, led to one of the strangest rumors about me that I’ve ever heard. Spread mostly by people who had not known me before, the rumor stated that, along the lines of 21 Jump Street, I was a narc, planted in the school to root out my classmates who were selling drugs. This, of course, was not true, though it was true that the neighborhood in which I lived, being on the border of Queens and Nassau County, was at the time one of, if not the primary conduit through which drugs traveled from New York City to Long Island. Ironically, in the months after graduation, an undercover narcotics squad conducted a huge sting operation just a few blocks away from where I lived. They arrested more than a few of the kids who were in my graduating class.

§§§

One of the most embarrassing moments of my senior year in public school took place in AP English. We were discussing “To His Coy Mistress,” by Andrew Marvell. Our teacher asked if anyone knew the biblical reference in the last couplet:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.

I was the only one to raise my hand. I doubt I remembered the specific chapter and verse, Joshua 10:12–14, but I did know that the lines refer to the battle between the Israelites and the Amorites, in which God gave Joshua the power to tell the sun to stand still until the battle was done and the Israelites were victorious. After I gave my answer, Mr. Giglio put his book down and looked disapprovingly over the class. “That story was part of Sunday’s reading in Church. How is it that this boy who does not even go to Church knew Marvell’s allusion, while not one of the rest of you did?”

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Late to the House of Words: Selected Poems by Gemma Gorga, translated by Sharon Dolin:

A reader will note a consistent interplay in [Gorga’s] work between the literal and the figurative, where everything is and is not itself. Thus, the “murky color” of the pomegranate’s stain on “our fingers” becomes the “open color of memory.” In her poem “Amusement Park,” the poet has a date with sadness, and while she conjures up the image of a ride on a Ferris wheel, she soon transforms it into an existential state: “How long have I been spinning round on this Ferris wheel,/now close to the world, now farther away?”

That’s from Dolin’s introduction, and it captures what was, for me, the most salient aspect of reading this book: the element of play that kept me interested from start to finish. And not just interested. It’s been a long time since I read a book of poems about which I could say, simply, that I enjoyed it at the level of sensual pleasure–and I include in this pleasure that which accompanies the intellectual and emotional leaps the reader has to make between the literal and figurative. I know Dolin’s work from Burn and Dodge, where she shows herself to be a meticulous craftsperson, a facility you can see at work in the sparse and carefully shaped lines of this translation. That level of care and attention to detail is what allows the play—of language, of ideas, of metaphor—at work in the center of Gorga’s poetry to be, simply, seriously, deeply, the pleasure that it is. The poems definitely deserve more than one reading. This was one of my favorites:

So Then She

With flour and water she worked

his body. With flour and saliva

she conceived, leaned, learned

that with flour and both hands you reach

the secret pliability of matter.

With flour and lips she worked

the man down to the unbearable

elasticity of tenderness.

The slowly she tasted

his body, the bread that was his body,

bread that fit as well in her hands

as does light on earth.

§§§

What’s The Meaning of Hanukkah?, by Mendele Moykher-Sforim, translated by Ri J. Turner:

“Anyway, the slap itself,” Shmuel went on, “wouldn’t even be worth mentioning if it hadn’t ultimately caused an upheaval that led me to discover new ideas. Basically, the slap I received from my father was not in vain. The whole discussion of Hanukkah, my father’s anger, the unexpected slap—it all remained vivid in my memory and drove me at quite a young age to chew on the question, ‘What’s the meaning of Hanukkah?’”

This story—the source does not give the date of original publication, only that it can be found in volume 9 of Moykher-Sforim’s collected works—devolves upon the kind of question that would lead many teachers to characterize the asker as a smart-ass: “The story about the single jar of oil that should have lasted only one day but lit the sanctuary for eight didn’t make [any] sense. If that’s how it happened, then the miracle itself only lasted for seven days—so why introduce an eight-day holiday?” That question leads the narrator to open “an extra-canonical book—a book of Jewish history,” and it’s there that his “eyes were opened and [he] found an answer” to the question which gives the story its title. I don’t want to say more, because I think part of the story’s genius is that the narrator does not articulate this answer himself. Rather, Moykher-Sforim leaves it up to the reader to figure out what the narrator means. The only caveat I will add is that the story does assume a knowledge of Jewish culture, nothing that isn’t easy enough to look up, though I think it’s possible to understand the story without doing so. Much of the story’s humor is embedded in that cultural knowledge.

§§§

The True Glory of the Maccabean Revolt: What Liberty was Fought For?, by Theodor Gaster:

Thus, the [Maccabean Revolt] had two objectives. First, it was designed to safeguard the actual identity of the Jews… Second, the resistance was designed to safeguard the constitutional status quo. In this, Mattathias and his followers were championing a cause which, transcending the particular interests of the Jews, extended also to all the national groups within the empire.

Years ago, at a gathering of my wife’s family that happened around Chanukah, a woman who was not Jewish apologized to me for not wishing me a happy holiday because she refused to celebrate an imperialist, nationalist holiday. She did not need to tell me, because I already knew her well enough, that this “apology” emerged from her anti-Zionist critique of the State of Israel and her corresponding support for Palestinian liberation. I did not bother to argue with her for two reasons. First, because I knew that pointing out the ahistorical nature of her position would do no good and, second, because it would be pointless to deny that Jews often do, very publicly, frame the existence of the State of Israel as being precisely the kind of thing that the Maccabees fought for. I have neither heard or read anyone making that kind of argument these days, which doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, but I take it as a hopeful sign nonetheless, especially given the ongoing devastation Israel is unapologetically wreaking on the Palestinians. Still, I was glad to come upon this article, from the December 1952 issue of Commentary. Especially towards the end I found much to disagree with (in no small measure because the world is very different seventy plus years after it was published), but Gaster does two things that I think are especially valuable for today. First, as I allude to in the quoted portion above, he points out that the oppressive policies under which the Jews suffered were targeted not only at Jews, but at all religious groups that were not part of Antiochus’ state church, formed in pursuit of (an enforced) political unity that had not previously existed and that he hoped would present “a united front against the ambitions of Rome on the one hand and of the rival power of the Ptolemies on the other…” Second, Gaster reminds us that the Maccabees were neither a majority movement within the Jewish community nor what we would call progressive, or even liberal, in their ambitions. In fact, given the ways in which they forced other Jews to practice as they did, the Maccabees had a lot in common with what the religious extremists of today say they want. It’s important, in other words, not to romanticize the Maccabees by turning them into the kind of liberators we would want them to be; and it is equally important to remember that, while they were unquestionably fighting to free the Jews from Antiochus’ oppression, they also understood, at least according to Gaster’s analysis, that their freedom to practice Judaism on their own terms was inseparable from the freedom of other religious communities to practice their faiths in the same way.

§§§

Rest in Power: A Running List of the Preventable Deaths Caused by Abortion Bans, Roxanne Szal:

These women should be alive today…Ms. is marking [their] stories. This article will be updated to mark every single name made public.

I don’t think I need to write much more than that quote. It is important to read through this unconscionably-too-long list and to remember as you do so that, as Szal puts it, “[T]hese are likely not the only cases, as there has been a significant increase in maternal mortality rates in states that implement strict abortion bans.”Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

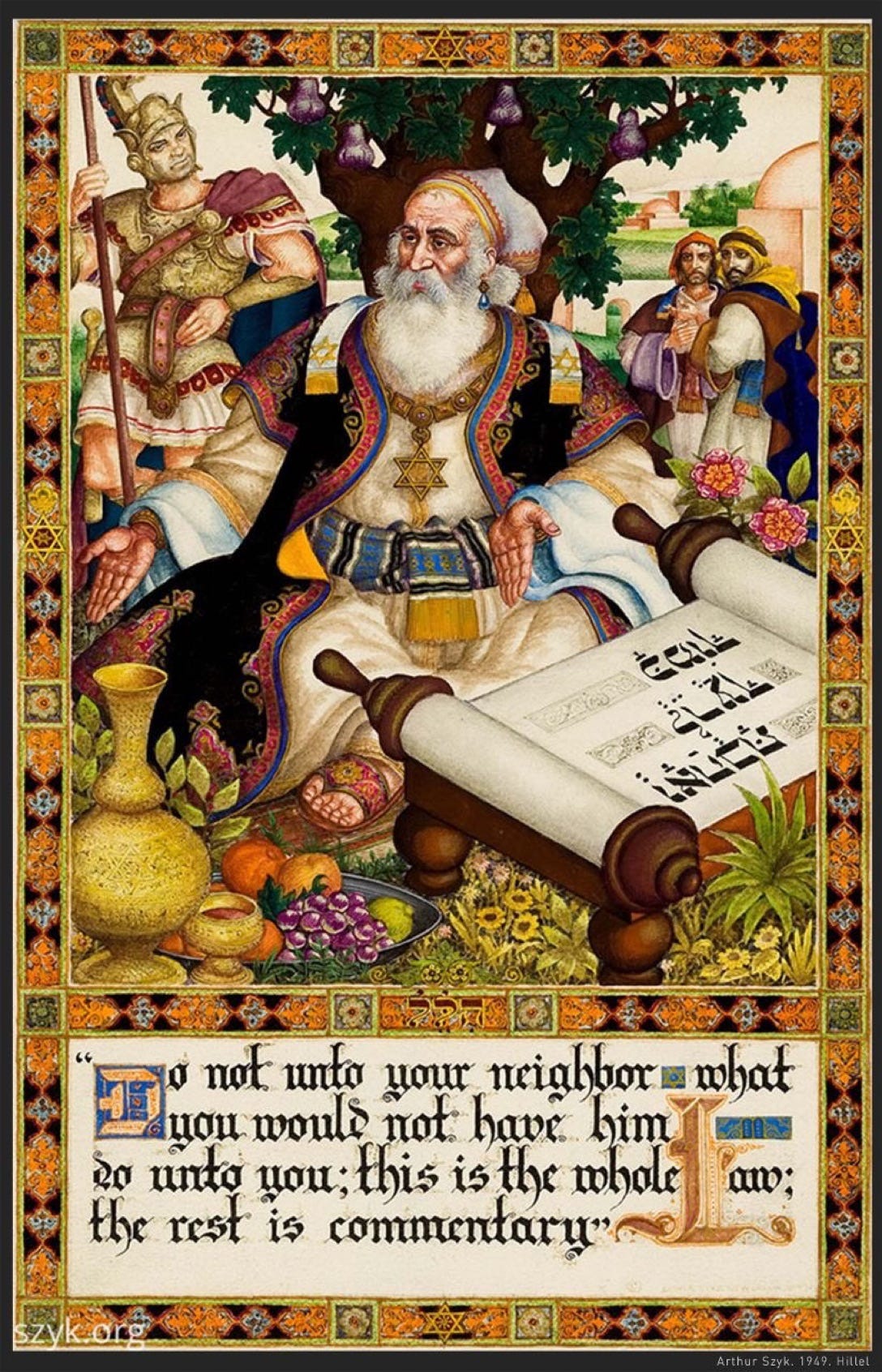

All these images are posted on X by Jewish Art:

§§§

§§§

Note the difference between the way Hillel states “The Golden Rule,” in the negative (Do not unto your neighbor), and the positive statement that is more commonly quoted (Do unto your neighbor).

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

My father and I did not speak for about ten years, from the time I was twenty-one or twenty-two until I was in my early thirties. Much had changed in my life during that time–I’d gotten married, for one–and so there was a lot about me that my father didn’t know. One of the ways I tried to catch him up on the person I’d become, as it were, was to give him a sheaf of poems that I’d written during those years. I had no idea how he would receive them or what he would think of my being a poet—he worked on Wall Street and was not much for the arts—but the conversation we ended up having surprised me in a way I could never have anticipated. We were walking somewhere in Manhattan, when he turned to me and said—and I promise you this is how my father really talked—“I read your poems. I also gave them to Alline [his wife] to read, since, you know, I’m not much of a reader. She and I talked about it, and I have to ask you a question. It’s kind of a joke, but it’s also not, if you know what I mean. So here’s the question, and I guess I’ll understand if you don’t want to answer at all, but remember, I am kind of joking when I ask this, even though I’m also being very serious. There’s a line in one of the poems you wrote when you were teaching in Korea, something about ‘the bodies I have buried in my imagination.’ Did you actually kill someone when you were teaching there?” The poem itself is long gone, and I remember nothing else about it except that line, so I can’t tell you whose bodies they were, if they were identified at all, or what happened to them. All I can say, since I know I did not commit murder while living in Seoul, is that they were, and should have been clearly recognizable as, a metaphor. My father, however, was not interested in talking about why or how he had misread my poem. All he wanted to know was whether I’d left a pile of bodies back in Korea when I came back to the United States. So I reassured him that I hadn’t, and that was the first of only two times that we ever discussed my work as a writer.

§§§

The second time my father and I talked about my writing, was in the Union Square Barnes & Noble. We were standing in the children’s section, watching my son lead my wife around to the different bookshelves. He loved bookstores, my son, so much so that when we took him to the ones closer to our home, we were often the last customers in the store. Anyway, I needed to use the bathroom, which was on the same floor as the poetry section, so when I was finished, I went to spend a few minutes checking the shelves, just to see if there was anything interesting. I was happily surprised to see a copy of Beyond Lament: Poets of the World Bearing Witness to the Holocaust, an anthology in which some of my poems had been published. I took the book upstairs to show my father, thinking he’d get a kick out of seeing my name in a book being sold in an actual bookstore. I handed the book to him, opened to the page where he could see my name. He smiled, made a show reading one of the poems—in reality I could see that he’d scanned the page and nothing more—and said, “Wow, Rich, that’s really deep.” Then my father did something that I still don’t fully comprehend. He closed the book, glanced left, then right, and then left again. Leaning towards me as he held open the left side of his London Fog raincoat, he gestured with his eyes towards the inside pocket, saying sotto voce, “You know, Richie, if I were a younger man…” and he inclined his head ever so slightly to the left, making it clear, if I hadn’t gotten it before, that the impulse to steal the book that he was choosing not to act on was a sign of respect for the fact that my work had been published within it. That was the last time I ever spoke with my father about my poetry.

§§§

It’s one thing to know that sexist erasure exists, to read about it, learn about its mechanisms, and so on. It’s quite another thing to watch as it happens before your eyes. Built in the 1920s, the co-op where I live in New York City is a historical landmark that went into receivership in the 1930s, during the Depression, and remained a rental property until the 1970s, when a group of tenants organized themselves to transform the place once again into a co-op. My grandmother was central to that effort. Not only was she involved in the whole process of incorporation; she was also the co-op’s first manager and the first president of the board. She was also intimately involved in the Garden Committee from its inception. The co-op recently celebrated its 100th year anniversary with a big celebration that included not only a party for shareholders, but, given our buildings’ historical significance, proclamations from local politicians. In the run-up to the celebration, one of the organizers got in touch with me to ask if I had any pictures of the grounds from my grandmother’s time. I did not. Based on that question, though, I assumed that the organizers—some of whom were old enough to know better than I how deeply involved my grandmother had been—were of course going to include her in whatever programming they had planned. I was wrong. On the day of the celebration, as I walked around, I met more than a few people who remembered my grandmother and all the work she did. Some of them had known me when I was a little boy. When it came time for the speeches, however, and for the proclamations, not one person mentioned my grandmother’s name among the list of men who were being remembered, nor did any of the people who knew her back then seem to notice, until I mentioned it to one of them. She was appropriately surprised and embarrassed by the omission, and she said she was going to rectify the situation. I have not heard from her about it, though, and so I am assuming nothing was done. What is clear to me, though, is that, had my grandmother, the only woman among the men who’d been honored, also been a man, she would not have been left out in the first place.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Ghost candles in the glass.

“We must not fear repetition in poetry,

because sweet speech is pleasant in the repetition.”

Nasir Khusraw, translated by Alice C. Hunsberger

Just got my copy of Rob Van Vliet’s (@rnv) new book, Vessels. Here’s a sample:

5 July

No matter how many times I asked,

the instructions were no help. So I stood

by the window, watching the buses pass,

all bound for parking lots as empty

as a table after the eviction.

And as the day began, I could still see

some stars, as surprising as

catching a handful of small

water-bugs skating on a lake of ash.

“It is [an] irony of oppression that the solution chosen to eliminate an enemy often guarantees that enemy’s enduring fame. [N]o one knows the names of [Nasir Khusraw’s] oppressors, but his poems…speak across centuries…to anyone who has [known] war, oppression or terror.”

It’s funny the things you find searching through old files. A long time ago, I collaborated with an artist named Allen Hart on an exhibition pairing one of his paintings with one of my poems. This was the painting, along with the broadside of the poem I made to put on the wall next to it.

Summer People, by Sara Hosey: This YA mystery tells the story of how Christmas Miller, a seventeen-year-old with ADHD, helps to save her upstate New York community, and at least potentially to begin to save the increasingly polluted lake at its center. A couple of things stood out for me. The tale is very well plotted, especially the way it holds until almost the very end the tension between Christmas and her best friend Lexi—the result of a falling out near the beginning of the novel—by keeping that tension almost wholly within the ADHD-shaped processing that goes on in Christmas’ mind. Indeed, overall, one of the more moving aspects of the way Hosey has crafted the narrative is the way she allows the plot to unfold through Christmas’ eyes so that the reader’s understanding of what is going on is shaped by the character’s ADHD—or at least that was my reading experience and one of the things that kept me turning the pages. It’s also impressive how many really important issues Hosey weaves seamlessly into the narrative, including climate change, homophobia, drug and alcohol addiction, the gentrification of upstate New York (though this is perhaps the most subtle), and how we view people with learning disabilities like ADHD. If you’re an adult reader, don’t let the YA label put you off. The story is a good one on its own terms, but if you want to be reminded what it was like to be a teenager, this is worth reading; and it’s definitely a book worth giving to a teen, especially one with ADHD, who I am sure would appreciate reading a book in which someone like them turns out to be the hero.

§§§

Joan of Arc: A symbol of fascism or feminism?, by Halima Jibril:

“Despite her short time on earth, Joan continues to have a long and complex afterlife. She has been everything: a proto-feminist, a rebellious teenager, a genderqueer martyr, a pious young woman, and, alarmingly, a symbol of far-right nationalism. Her legacy is complex and multifaceted, often viewed through a narrow lens – either feminist or fascist.”

I haven’t thought seriously about Joan of Arc and what she stood/stands for in decades, not since I read, of all things, Andrea Dworkin’s Intercourse back in the late 1980s. In chapter 6, titled “Virginity,” Dworkin writes about Joan of Arc’s decision to remain a virgin as

a self-conscious and militant repudiation of the common lot of the female with its intrinsic low status…Her virginity was an essential element of her virility, her autonomy, her rebellious and intransigent self-definition. Virginity was freedom from the real meaning of being female; it was not just another style of being female.

Dworkin’s focus in that chapter is a kind of cultural history of the idea of female virginity, but the use she makes of Joan of Arc as an icon of feminist rebellion against the patriarchy fits perfectly into the history Jibril traces in her article. The part of the article that was new to me is how the right wing in France has used Joan of Arc as a symbol of its fascist agenda.

§§§

Tentative Thoughts On The Jewish Claim To A "Religious Abortion”, Josh Blackman:

For Christians, perhaps, quantifying the consequences of committing a sin is easier. For Jews, however, the issue is far more complicated. Judaism is not a centralized religion. There is no Jewish equivalent of a Pope. We often speak of “Orthodox,” “Conservative,” and “Reform” Jews, but even within these categories, there is no official or standardized set of teachings. Every Congregation, indeed, every Rabbi, may follow the teachings in different fashions. Moreover, every Jew can look to faith in his own fashion. And there is no obligation to be consistent. A Jew could hold one opinion in the morning, and then change his mind over lunch, and go back to the original position after dinner. The old saw, Two Jews, Three Opinions, is apt.

This article is from 2022. It was written in response to a challenge brought by Congregation L’Dor Va-Dor, a synagogue in Palm Beach County, Florida, against the constitutionality of what were then the state’s new abortion restrictions. Basically, the congregation’s argument centered on the fact that Judaism does not prohibit abortion in the same way that Christianity does and that, since there are situations in which Judaism mandates abortion, or at least makes it religiously available to women in ways that Christianity does not, a law that makes abortion illegal would violate Jewish women’s religious freedom. (Two books that are worth consulting if you’re interested in the differences between Jewish and Christian positions on abortion are Marital Relations, Birth Control, and Abortion in Jewish Law, by David M. Feldman and Women and Jewish Law, by Rachel Biale. The differences are significant and worth knowing.) Independently of whether or not the synagogue’s claim has any legal merit, though, what I find deeply disturbing about this article is how blithely dismissive Blackman is, in the paragraph I’ve quoted above, of Judaism and the religious culture intrinsic to it and the way he tries later on in the article—intentionally or not—to define Orthodox Judaism as somehow more authentic than any other form of Jewish religious practice. It is part of a troubling trend I have seen elsewhere in which the Orthodox are defined—and sometimes define themselves—as the “true” Jews, basically stripping, or trying to strip, Jewish identity from the rest of us. I am sure Blackman would say this is not what he was trying to do, but his reasoning throughout the article, at least as I read it, is implicitly Christological, by which I mean it takes Christianity as the normative framework to apply to all religious practices. Judaism, simply put, does not, not in any of its sects, fit that framing.

§§§

It’s Time to Talk About Pornography, Scholars Say, Matt Richtel:

In February, Dr. [Beáta] Böthe was an author of a paper that found that some types of pornography could affect the sexual well-being of viewers. The study, a survey of 827 young adults, found that people who watched passionate or romantic pornography reported higher sexual satisfaction in their relationships, whereas watching “power, control and rough-sex pornography was associated with lower sexual satisfaction.” (The study also noted that the passionate, romantic and multipartner material was more widely viewed than the harder-core categories.)

While it is long past time that we should be talking openly about what the scholars Richtel talked to call “porn literacy,” what I find most interesting, and frustrating, about this article is the challenge of creating any kind of coherent picture from the very different results of the various studies that Richtel cites. So, for example, in addition to the one I quoted above, there is the 2021 study of 630 Dutch, which found that “adolescents who watched more pornography engaged in more advanced sexual behaviors at a younger age” but could not determine “whether more sexually advanced adolescents were drawn to pornography or whether the pornography drove their behavior.” Then there is the fact that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “as pornography use has grown among American adolescents, young people are waiting longer on average to experiment with actual sex.” Then, when you consider that, according to a 2023 survey of adolescents by Common Sense Media, Americans first see online porn when they are 12 and that 73% of those 17 and under have seen it, and that more than half of those who watch porn “reported seeing violence, including rape, choking or someone in pain,” how do you not wonder how to make sense of what the studies tell us. One paper cited by Richtel suggests getting primary care providers involved in “assessing [pornography] use and providing sexual health education.” I understand the impulse, but I am very leery of what the unintended consequences could be of medicalizing pornography use in that way.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

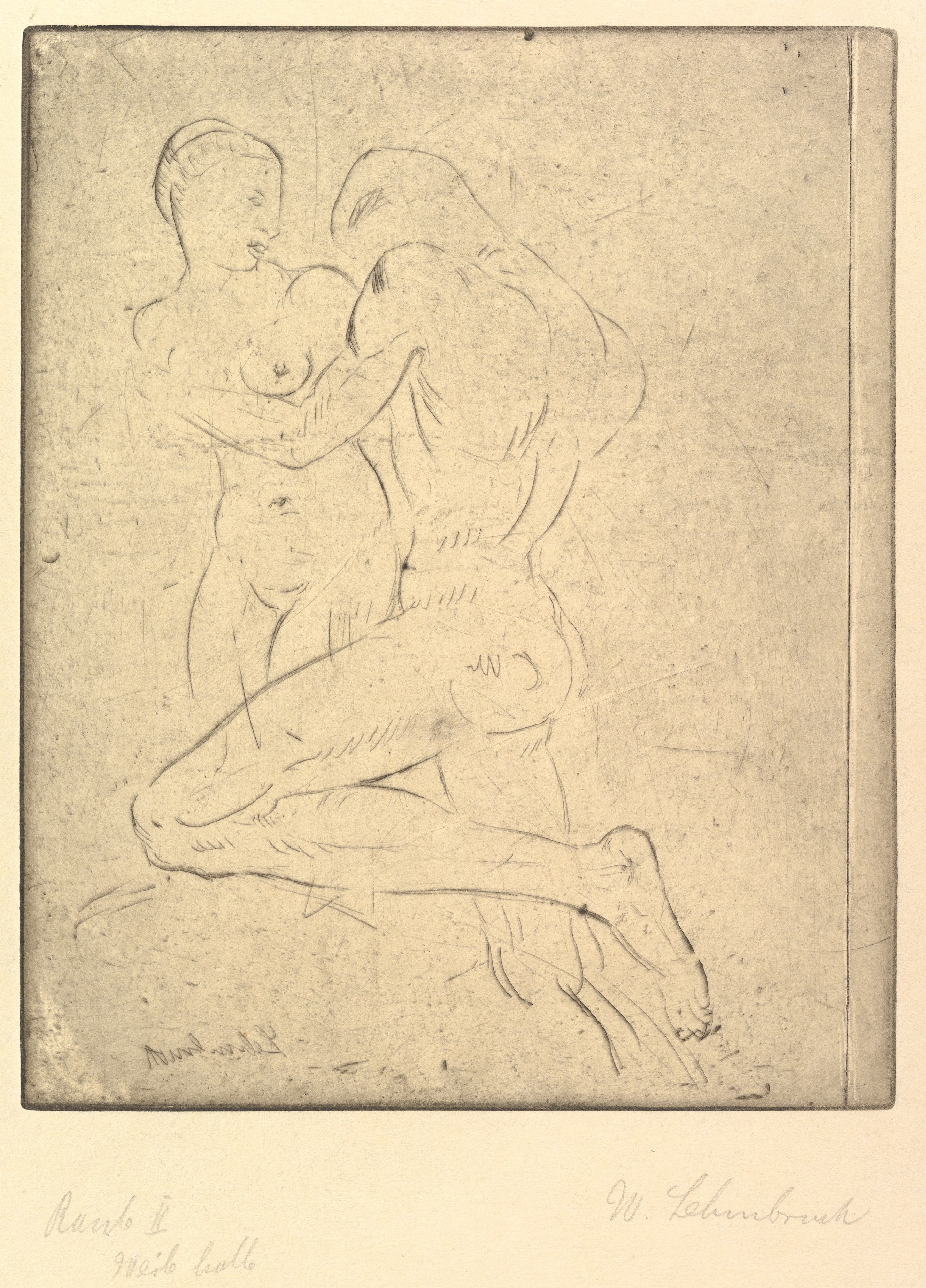

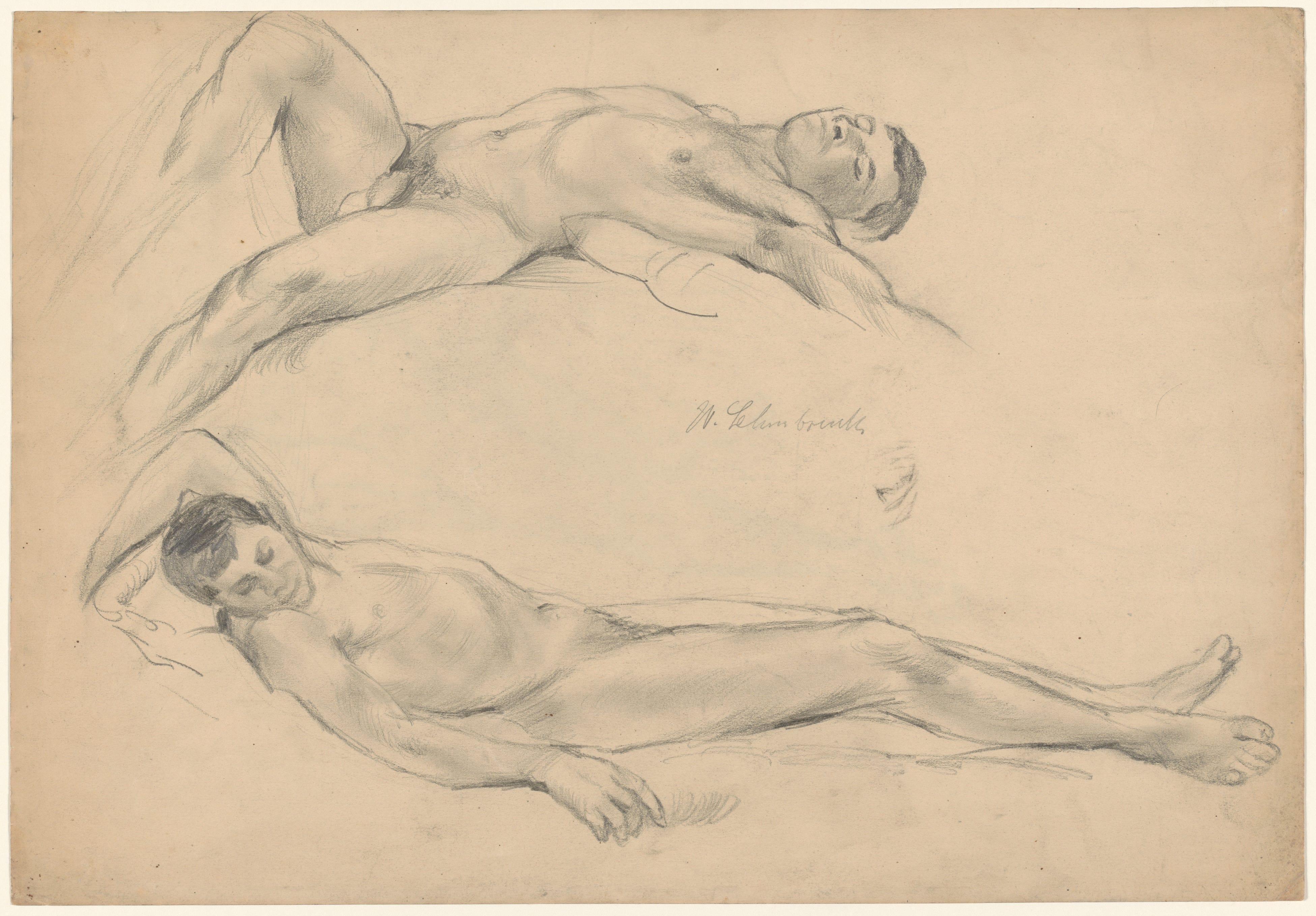

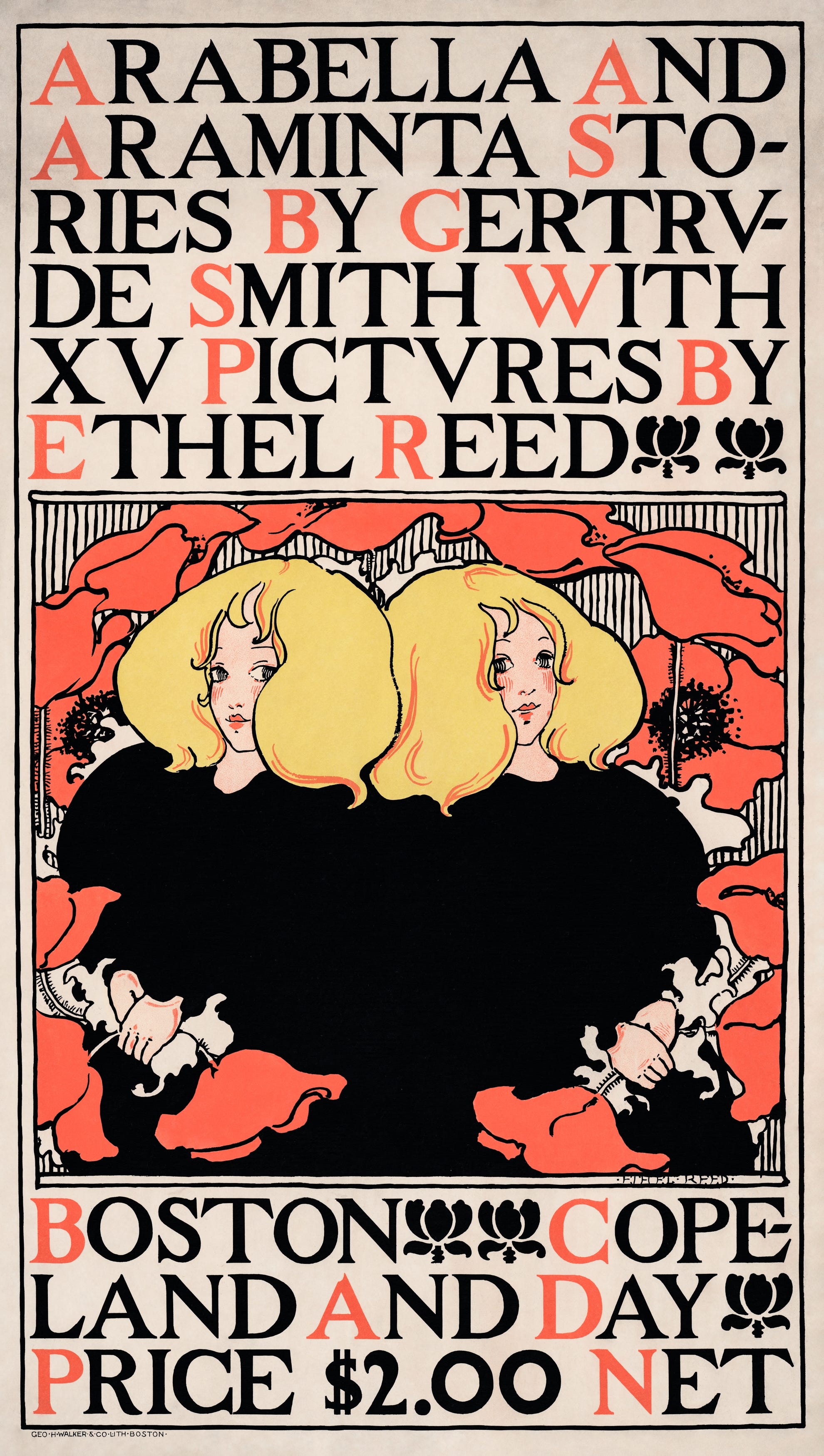

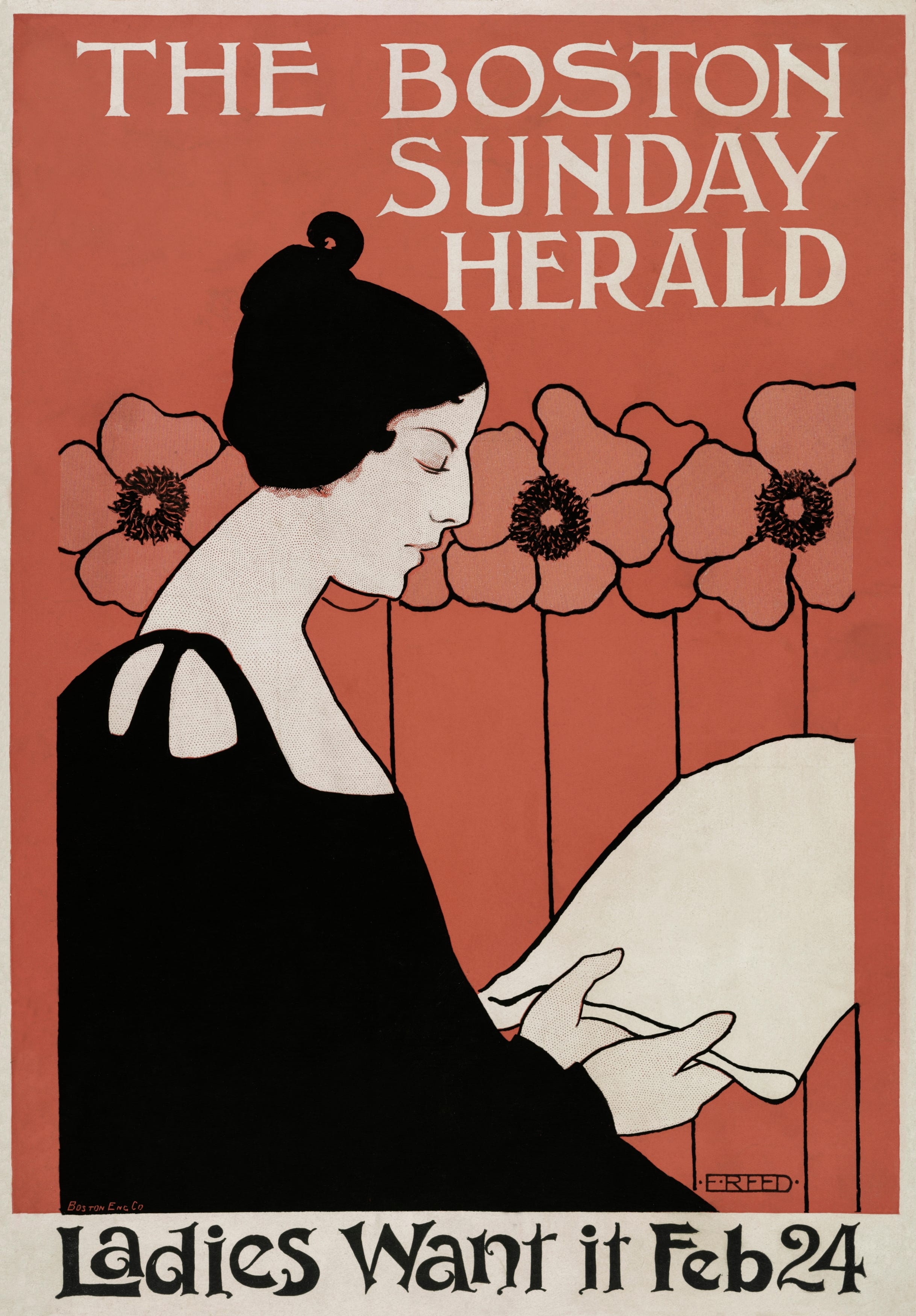

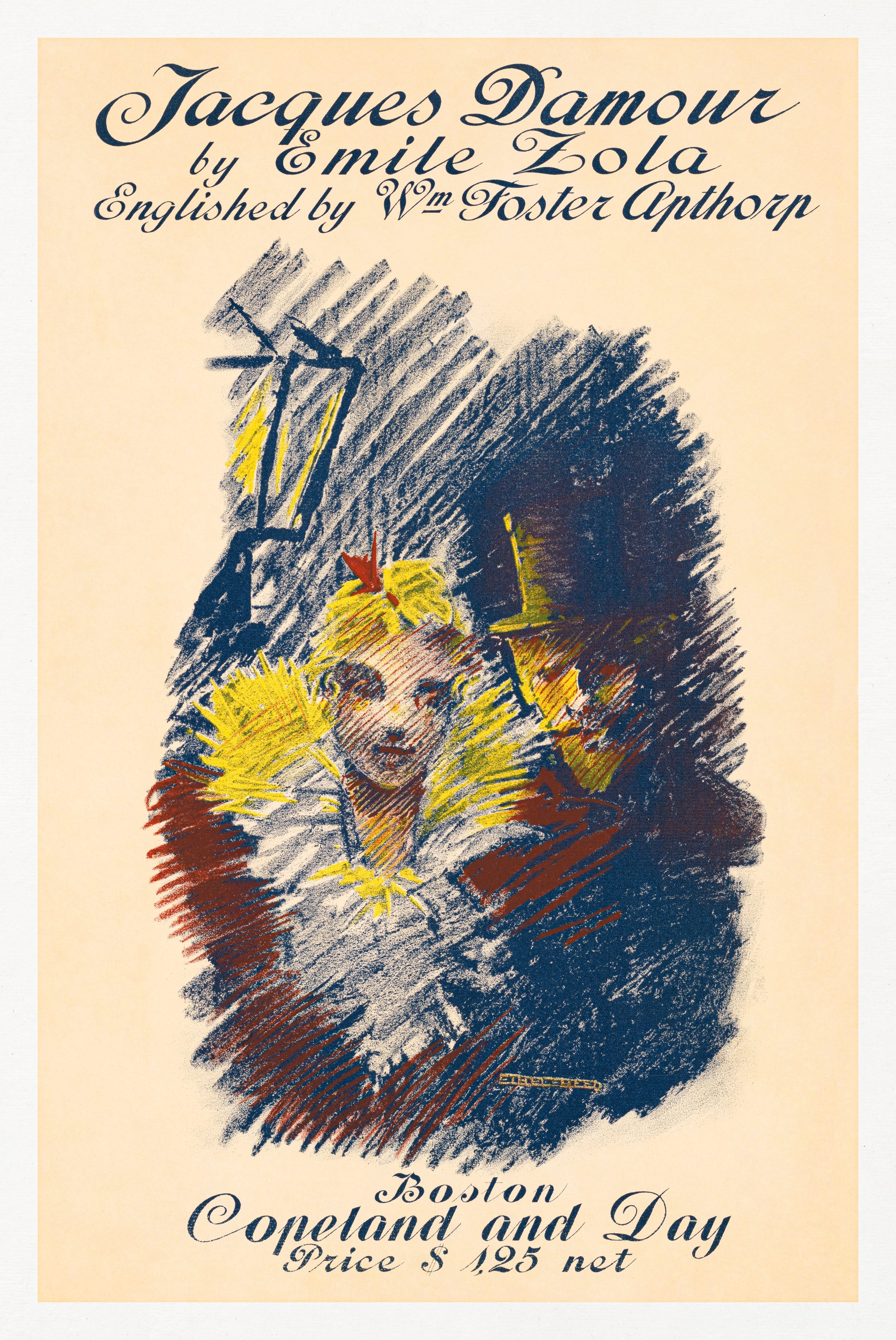

These images, all in the public domain, are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

“Zog es mir nokh amol,” with lyrics by Jacob Jacobs, is a song from Ellstein and Israel Rosenberg’s operetta Der berditchever khosn (The Bridegroom from Berditchev). You can find a synopsis of the show here. It’s an interesting look in to a Jewish way of life that doesn’t really exist anymore, at least not in the mainstream. I’ve put a translation of the lyrics below the video.

If I would only be fit

to find favor in your eyes,

the whole world would already be mine.

I would sing “Hatikvah” [Become a Zionist]

and would even go to the mikvah [be religious],

just so you will be together with me. I would cut a deal

to become a slave to your father,

like Jacob was to Laban.

I would suffer all kinds of terror

and would even milk the cows,

so long as I would always be able to see you.

Tell me again,

oh, tell me again,

for I’d like to hear

those beautiful words from you.

Tell it to me again,

oh, tell it to me again,

for your words bring me joy

and give me constant encouragement.

My heart is overflowing

with such great joy

of having lived to hear

such words from you.

Tell it to me again,

oh, tell me again.

Oh, my heart, my dear,

Tell it to me again.

—translated by Eliyahu Mishulovin & Adam J. Levitin

§§§

I wrote about the first time I got high back in Four By Four #12. I was seventeen, which was late among my peers, and I asked my friend Joey to get some pot for us. We smoked it in my bedroom one afternoon when no one else was home. I did not feel a thing, which Joey told me was normal, saying that if I wanted to try again, I should just let him know. I don’t remember when or where the second time was, but I do know that, again, it was just Joey and me and that, this time, I did get high. I didn’t like it or dislike it, but the feeling was interesting, and I do remember thinking that it would be nice not to be the one always turning down the joints that got passed around when my friends hung out. One day, two of the girls who lived in our development—one was named Kim; I don’t remember who the other one was—asked me if I wanted to smoke with them. I said yes, but instead of the mildly pleasurable experience I’d come to expect, what I went through was scary enough that it put me off getting high pretty much for good. I don’t remember much in detail, but at some point after we’d finished the joint the girls and I shared, I began to believe, truly, that my heart was slowing down and that if I wasn’t careful—if, for example, I fell asleep—it would stop beating and I would die. I remember going home, closing my door, and pacing the length of my room, rubbing my arms and legs to keep the circulation going. I was terrified. I have no memory of what happened between the moments of my pacing and whenever the high wore off, but when I saw Kim the next day and told her about my experience, she informed me that she and her friend had “dusted” the pot, meaning that they’d laced it with angel dust. That was my introduction to PCP (the abbreviation for phenylcyclohexyl piperidine, which is angel dust’s chemical name), a drug that at least one of my high school classmates would OD on the year of our graduation. I stopped smoking pot after that, with one or two exceptions. Each of those times, though, I felt like I was having flashbacks, and so I stopped smoking entirely.

§§§

When I was in eighth and ninth grades, my friend Amy and I would pass notes in math class, but we didn’t write those notes on slips of paper. We actually had a notebook we passed back and forth between us. The first notebook we used had a green cover and so we called it our “little green notebook.” I don’t remember who that first one belonged to, but I’m pretty sure that I bought the second one because I remember being in a store somewhere trying to find one the same shade of green as the first. I don’t remember if we ever got caught, but I do remember Amy loving the music of Chicago, which I came to love too, especially, once I started playing bass baritone bugle in my hometown drum and bugle corps. Amy and I connected for a while on Facebook, where I was surprised to learn that she had not only been a Dead Head at some point after high school, but that she had also chosen to live an orthodox life in Israel. She moved there, she told me, though I have no idea how long ago, because of the unrepentant and persistent antisemitism she, and particularly her children, experienced where she and her family were living. I could identify with that feeling, but I was surprised that she’d become orthodox. I remember her being quite a rebel when we were kids.

§§§

When I was in college I worked part-time as an advisor for a local Jewish center’s youth group. I was maybe twenty years old and just beginning to question the narrative I’d been taught about Israel and the Palestine. I don’t remember when or why, but at some point while I was still working there, the director of the youth group and I were having a discussion about Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. I was making a point that had something to do with how Israel exploited Palestinian labor. I didn’t put it in those terms, of course—I wouldn’t have known those terms back then—but I know I said something about the low wages the Palestinians were forced to accept. In any event, what has stuck in my mind all these years is the youth director’s response. “I’ll say this to you here because it’s an internal conversation. You’re right that it’s not fair”—I am paraphrasing, of course—“but if that’s what Israel needs to do to build itself up, then that’s what we need to do.” It was the first time I’d heard anyone, much less a Jewish adult, admit that Israel was anything other than morally correct in its treatment of the Palestinians, but what was shocking to me was how easily he endorsed that behavior as a necessary evil we as Jews should be willing to live with. In some ways, the evolution of my views on Israel and Palestine began with this conversation.

§§§

When my son was little, my wife and I made the conscious decision that he should learn to speak Persian, which is my wife’s native language, especially so that he would be able to communicate with his grandparents and other relatives who did not speak English. At the time, I learned enough Persian that we could speak only, or at least primarily, Persian with our son, though once he got to be about four years old, not only was my Persian insufficient for our communication needs. He started not to accept Persian from me at all. Two things have stuck with me from that time. First, the number of people who worried that my son would grow up to speak English with an accent because he spoke Persian first. They were well-intended of course—or at least they thought they were—but the response is actually an irrational one, borne more of the fear that someone like my son would be marked by his “flawed” speech as not fully American, and at least implicitly as not white, than of any real knowledge of how child language acquisition works. The second thing that has stuck with me is the number of people, all of them non-Jews, who wanted to know why I did not insist that he also learn Hebrew, the assumption being that, because I am Jewish, Hebrew is somehow my language in the same way that Persian is my wife’s. Unpacking the assumptions knotted into that question is probably an essay unto itself, but they are the same assumptions, I think, that underlie the line some people have used to defend themselves against charges of antisemitism: “I can’t be antisemitic; I support Israel.”

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

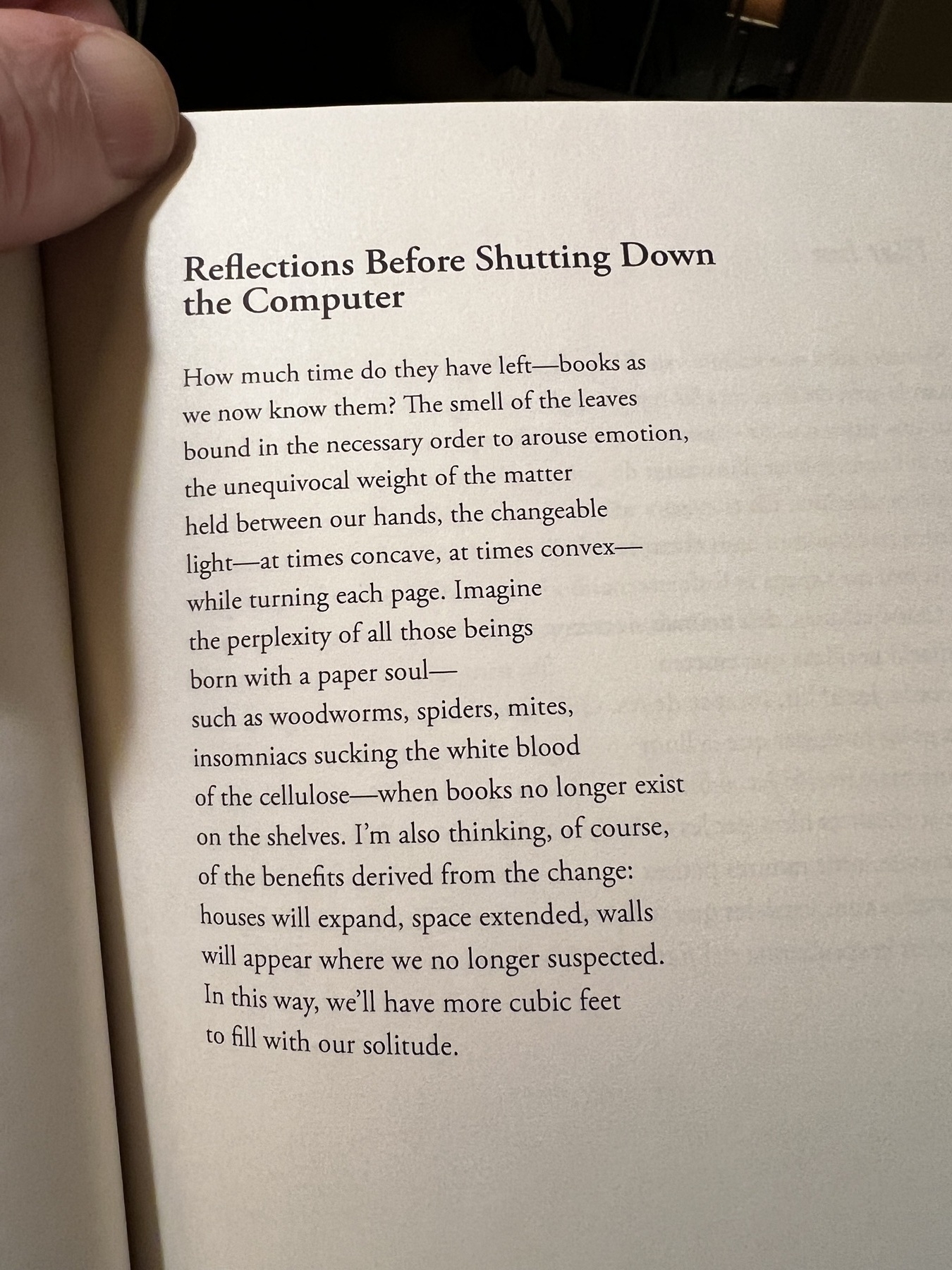

“Reflections Before Shutting Down The Computer,” by Gemma Gorga, translated by Sharon Dolin.

from “Reading Matsuo Bashō,” by Gemma Gorga (translated by Sharon Dolin):

I wonder: how many syllables must I remove

to make a perfect haiku from my life?

All The Ways We Lied, by Aida Zilelian: The last sentence of this novel is “Because after all, there was freedom in being loved.” When I read those words, I felt keenly how much I enjoyed and was moved by the winding path along which the novel earns that sentiment. The story revolves around a family that is, in many ways, on the verge of falling apart. The narrative traces the path by which they manage to stay connected to and committed to and loving of each other by individuating, finding out who they are as people not wholly defined by their (sometimes comically rendered) deeply dysfunctional family dynamic. If you’ve ever had to figure out how to love someone who seems hell bent on making it difficult to love them—and especially if you have any experience, vicarious or otherwise, with how that dynamic can play out in an immigrant family—you will both enjoy and identify with the four women, a mother and three sisters, who are the main characters of this book.

§§§

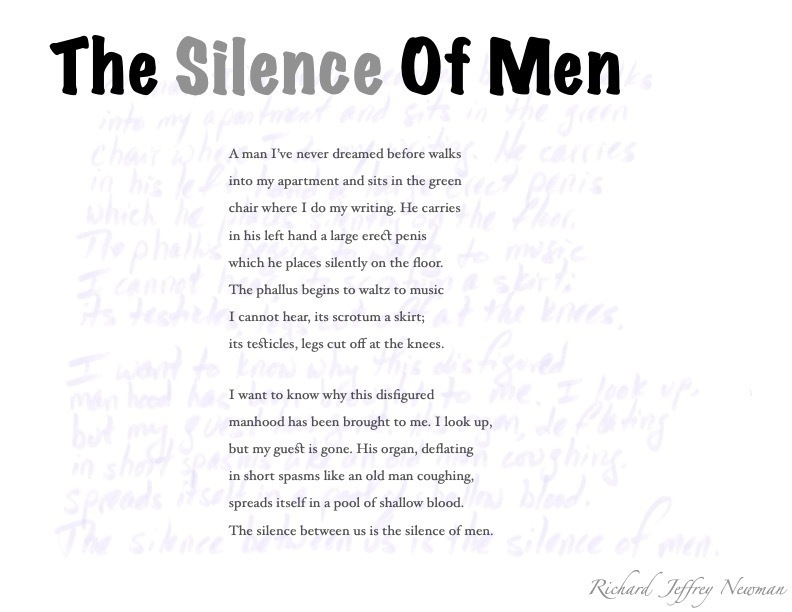

The Room Where I Was Born, by Brian Teare: When CavanKerry Press published my first book, The Silence of Men, in 2006, I thought it was also the first book of poems explicitly to take on the experience of being a male survivor of childhood sexual violence. I was wrong. Brian Teare’s The Room Where I was Born, which I just finished and which won the 2003 Brittingham Prize in Poetry, preceded mine by, obviously, three years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we dealt with the subject matter in very different ways. Teare is concerned in his book with making poems that give form and meaning to the ways in which childhood sexual violence disrupts, corrupts, warps, and otherwise undoes the survivor’s sense of reality. Those poems are about naming that experience as much as they are about naming the experience of violation itself. The Room Where I Was Born also explores Teare’s coming to terms with being gay in the context of the sexual violation he experienced and the homophobia of both the place where he grew up and our culture at large. I am glad to have read this book, which was recommended to me by Rob Arnold, the executive director of Poets House.

§§§

The Spectre of Patriarchy, by Roberto de Mattei:

At this point, Prof Ricolfi poses an obvious question: how can one speak of a patriarchal society when the figure of the father has disappeared not only from the family but from society more generally?

Mattei wrote this piece in response to an editorial in the Italian newspaper I’ll Messaggero, by Professor Luca Ricolfi, a sociologist, who believes that “in Western societies the distinctive traits of patriarchal societies have almost entirely disappeared.” Ricolfi goes on to argue that violence against women is the “result…of the defeat of patriarchy.” It’s an important argument to understand, if only because I predict we are going to hear it more and more frequently here in the States in the months and years to come.

§§§

Facing 8 Years in Prison, a Director Flees Iran, by Amir Ahmadi Arian:

“[The Seed of The] Sacred Fig” offers [a] provocative exploration of…the myriad injustices Iranian women have to endure in their daily lives. “In my early movies, women were far from the center,” Rasoulof says. “At one point I looked back and noticed that I had not created a single round, compelling female character. I knew very little about women’s lives, and I decided to rectify that.”

This article, which tells the story of Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof’s career and his decision to escape from Iran, is also notable for its brief history of Iranian cinema since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. It’s worth reading for both.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

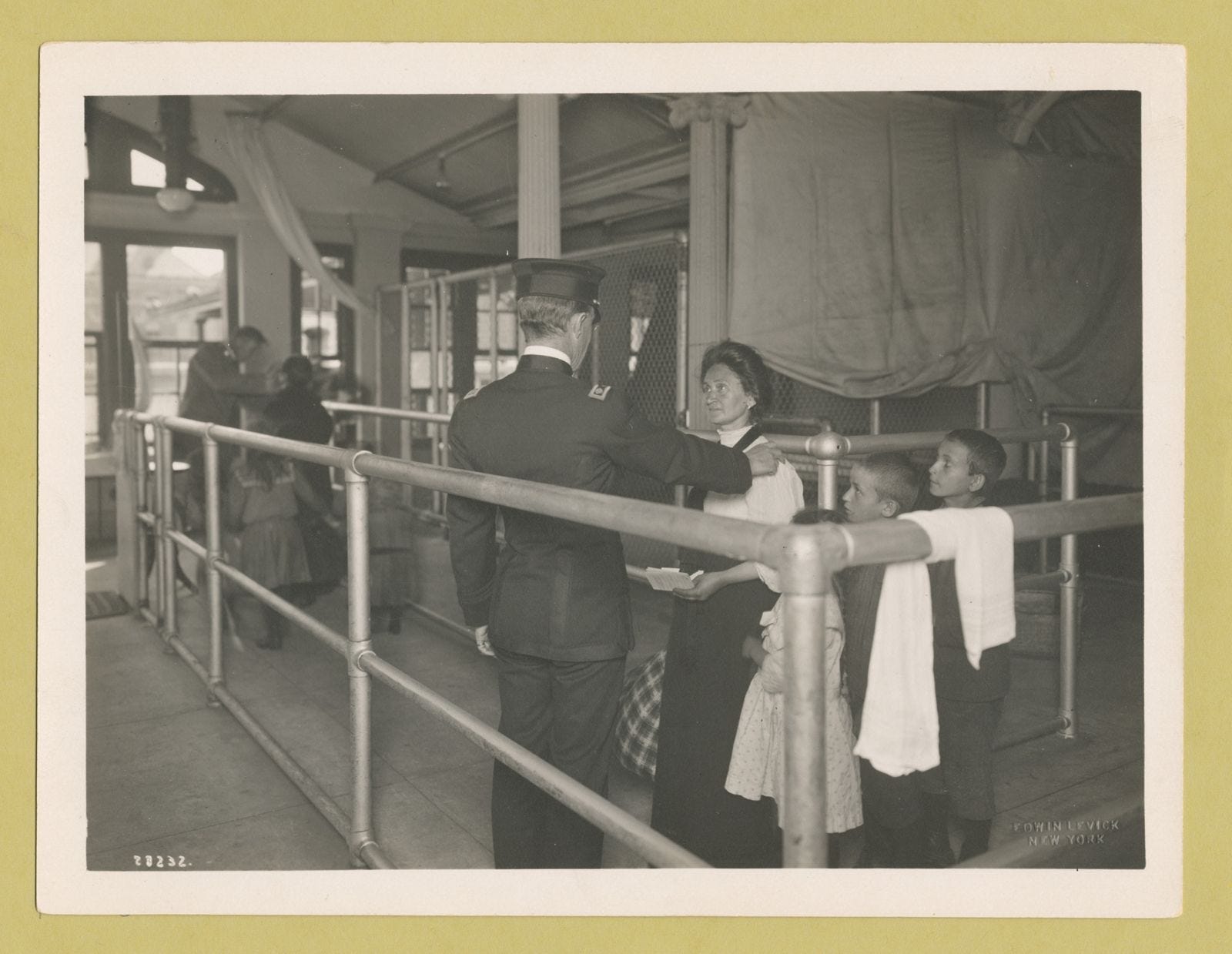

All images are from the New York Public Library’s Collection of Ellis Island Photographs taken between 1902 and 1913 and are in the public domain.

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

§§§

The first time I remember hearing the word period used to refer to menstruation I was in fifth. That week, the girls had been show a filmstrips about puberty. (The boys, because we were considered less mature than the girls, would not see it till the following year.) My friends and I were hanging out in the courtyard of the garden apartments where we lived, and one of the girls—I’m pretty sure it was Gina—started teasing us that boys “didn’t know what a period was.” I don’t remember anything about the rest of the conversation, except that Gina did eventually tell me—and I think she may have told only me—that it meant the monthly bleeding that began when a girl reached puberty. In my memory, this was not actually news to me, though I don’t remember why I knew about it. I had never before heard it called a period, though, and that seemed more strange to me than the biological fact itself.

§§§

Another encounter that I had with menstruation, probably around the same time, was at our neighborhood’s public pool. I have a clear memory of a Black girl in a yellow bathing suit walking with her mother away from the side of the deep end where I was swimming, while trying to cover with one hand the bright red stain that it was impossible to miss near her butt. Given how white and racist our neighborhood was, I find it hard to imagine that the girl and her mother were actually from the neighborhood—and, in fact, I am surprised that I have no memory of anyone saying anything to them. In my memory, though I have no idea how reliable this is, the girl is the daughter of my mother’s friend Vivian, who had come for a visit. What I remember most clearly, is feeling tremendous sympathy for how embarrassed the girl must have been as she and her mother walked to where their towels were so the girl could wrap one around her waist; and I remember as well feeling strongly how different my own body was from hers and how incomprehensible her experience seemed to me.

§§§

I fell in love in my twenties with a woman I was in a relationship with for around seven years. We met at the summer camp where we were both counselors and we very quickly became good friends. She was not-quite-yet-engaged to the man she thought she was going to marry; but she was, she explained, also seeing another guy who worked at camp, because she wanted to make sure that the first guy really was the one she wanted to marry. We were both very clear as our friendship developed that we did not want to turn that triangle into a square. Still, the more we talked, the closer we became, and she and I eventually ended up together. That didn’t happen at camp, though. We fell in love after engaging in what would have been a perfectly conventional Victorian courtship. After camp was over—and this went on for a couple of year, if I remember correctly—we wrote long letters in which we revealed ourselves in ways we would not have been able, and likely would have chosen not, to do in person. That kind of letter writing, not just between lovers, but between friends as well, was still common during my lifetime. I miss it. Email just doesn’t cut it.

§§§

I wrote in Four by Four #11 about Rabbi Wehl, the gemara rebbe in whose class I first learned the lesson of “loving the questions.” When it came to the question of how committed his students were to living his version of an authentic Jewish life, however, Reb Wehl could be a real son-of-a-bitch. At least once a week during the fall—or at least it was that frequent in my memory—he would go on a rant about how shameful it was (a shonda!) that our parents would spend twenty or thirty dollars on a turkey for Thanksgiving, but they wouldn’t spare a dime for a set of Mishneh Torah, Maimonides’ attempt to write a comprehensive treatment of all of Jewish law, including those laws that only applied when the temple stood in Jerusalem. At some point that year—this was 10th grade—he found a bookseller willing to sell his students a five volume set for five dollars. He put so much pressure on us that there was no way not buy a set, which I was reluctant to do because my Hebrew was nowhere near good enough for me to be able to read the book on my own. So I convinced my mother to give me the money. Every once in a while I would try to read it and then give up. The books stayed on my shelf for a long time before I got rid of them. While I am sure I did not throw them in the garbage, I have no memory of what actually happened to them.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

My translation of “Ibn Abd al-Aziz Sacrifices A Jewel,” which is from Bustan, by Saadi of Shiraz was publised recently in The Loch Raven Review. (The link will take you to the section of the issue devoted to Persian literature, but you need to scroll down three poems to come to mine.) The poem speaks to our current moment in a variety of ways, I think, but most clearly in terms of the ever growing wealth disparities in this country and around the world. This is the poem’s final couplet:

Those who value virtue will never buy

with others’ pain and sorrow their own joy.

Bernie Would Have Won, by Krystal Ball:

“The bottom line is this: Democrats are still trying to run a neoliberal campaign in a post-neoliberal era. In other words, 2016 Bernie was right.”

I’ve stopped reading and listening to most of the analyses purporting to explain the scale of Kamala Harris’ loss to Donald Trump in the presidential election, not because I think they are wrong, but because they often seem more interested in whatever stake they have in their specific explanation then in whether or not the explanation itself moves forward the larger conversation that clearly needs to happen. (John Stewart did a good job of skewering this towards the end of this clip from The Daily Show.) I know I’m being somewhat reductive here, because it’s not like sexism and racism and homophobia and the Biden administration’s enabling of Israel’s decimation of Gaza and its people, along with all of the other reasons being given for why not enough people who showed up at the polls chose not to vote for Harris, are irrelevant. Nonetheless, too few people are taking seriously the argument that Ball makes in this brief essay, which is that Harris lost because the Democrats rejected back in 2016 Bernie Sanders’ class-based analysis as a viable foundation for a presidential campaign. Ball makes a distinction between Trump’s populism and Sanders’ that I think is worth thinking carefully about. Because “right-wing populism embraces capital,” she wrote, “…it posed no real threat to the monied interests that are so influential within the party structures…The Republican donor class [may not have been] thrilled with [Trump] but they did not view him as an existential threat to their class interests.” Meanwhile “Bernie’s party takeover did pose an existential threat—both to [Democratic] party elites who he openly antagonized and to the party’s big money backers. The bottom line of the Wall Street financiers and corporate titans was explicitly threatened.” That’s why, Ball asserts, “His rise would simply not be allowed. Not in 2016 and not in 2020.” That difference mattered back then and its specter haunted this election as well.

§§§

Why Do Some States Protect Women While Others Enable Abuse?, by Alice Evans:

“Sexual liberation did not guarantee female safety. Young women wanted to enjoy the night like their male peers, but it remained very much a man’s world. Rapes and murders were frequently reported across major cities. A woman who attracted attention only had herself to blame: “What was she wearing?”, “Why was she out so late?” Objectors were derided as killjoys. This tension between growing freedom and persistent danger revealed a crucial truth: women needed both the liberty to move freely and the protection of strong institutions willing to defend their rights.”

Evans goes on to demonstrate that a primary reason the violent crime rate in the United States decreased, at least prior to 2014, including violence against women, was the fact that state institutions took seriously the notion that violence against women was not acceptable. In the rest of the piece, she goes on to talk about the relationship in several places—Russia, India, China, South Korea, and Latin America—between the relative success of campaigns against gender-based violence and the stance taken by governmental institutions, not just towards women’s rights, but towards democratic society in general. She also makes the point that even in countries where progress has been real, it is not inevitable, something to pay careful attention these days as the right both intensifies its attacks on women’s rights and celebrates notions of manhood and masculinity that are part and parcel of women’s subjugation.

§§§

Whispers, by Kamal Elgizouli (translated by Adil Babakir):

It’s not murder that I dread.

Not even a tragic end.

Nor this door being blown down outright,

or them storming in at midnight,

their naked guns in full sight.

No.

Not festering wounds, streams of blood,

or the wall dotted with fragments of my skull.

What I fear the most, I have to say,

is fear per se…

I needed this poem. It is easy to give in to fear these days. Donald Trump’s election, precisely because it was enabled by so many people voting against their own long-term self-interests, arguably embodies it. The lines that hit me strongest were there: “You are destined to die—and so are they./No one is exempt.” I’d prefer to let the poem speak for itself. I hope you will take a few minutes to read it.

§§§

‘Verbally Assaulted’ After ‘Shut It Down’ Reversal, U. of Michigan Student-Government Reps Demand Leaders Resign, by Katherine Mangan:

“The vote to restore funding, on October 8, had been a direct rebuke to the president of the Central Student Government, Alifa Chowdhury, who had carried through on an unusual campaign promise. She and the vice president, Elias Atkinson, were elected along with two dozen other representatives, on a platform called “Shut It Down.” It promised to deny funding to student groups unless and until regents agreed to their demands that they divest the university’s endowment from companies with economic ties to Israel. Similar demands have been at the center of nationwide campus protests over the Israel-Hamas war since last spring.”

This article, along with another one published in The Chronicle of Higher Education, “U. of Michigan Student Government Impeaches President, VP for ‘Inciting Violence’ Over Student-Fee Dispute,” also by Katherine Mangan follow up on something I shared with you back in Issue 26: “At Michigan, Activists Take Over and Shut Down Student Government.” I wrote then that I was fascinated by the then-newly elected student government’s tactic of holding student-club money hostage until the school divested from all Israel-related investments, not least because of the way it seemed to echo the strategy used in this country by the right to gain control of local government in order to push its ideological agenda. I wanted to share these follow-up articles with you.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

All images are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and are in the public domain.

Artist: Toussaint Dubreuil (French, Paris ca. 1561–1602 Paris)

§§§

Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn) (Dutch, Leiden 1606–1669 Amsterdam)

§§§

Costa Rica, 10th–16th century, from the Chiriqui culture

§§§

Manufacturer: Brewster & Co. (American, New York), ca. 1860, by William J. Rensler (artist) American, 1891 - 1946. Of all American carriage manufacturers, none was as highly regarded for design, finish and quality as Brewster & Company. They won many awards for outstanding workmanship, including the Legion d’Honneur (Legion of Honor) at the 1878 Paris Exposition (3rd World’s Fair). In appreciation for this achievement the Carriage Builders’ National Association presented them with a gold enameled Tiffany & Company plaque and autograph book signed by leading American carriage builders, both now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

§§§

§§§

§§§

I held two jobs after I dropped out of Syracuse University's Creative Writing MA program, each of which I have written about before. First, I was a Jewish Campus Professional for B'nai Brith Hillel/JACY, advising two Hillel groups on two different campuses. I left that job because my girlfriend at the time was not Jewish and I did not feel right promoting the organization's position against interfaith dating when I was actively violating it. (Interestingly, the woman who first got me into Jewish community work tried to persuade me that it would be okay for me to do that. She thought the value I brought to the community outweighed the fact that I was violating one of its most basic tenets.) Second, I worked as a writer for a competitive intelligence business, producing a database for CEOs to use in making strategic technology decisions for their businesses. I left that job because I realized I was not interested in working in a corporate environment and that, despite how unhappy I’d been teaching freshman composition as a Teaching Assistant at Syracuse, I really did want to teach. So, in 1986, I decided to pursue the linguistics half of my undergraduate double major—the other half was English—but instead of studying to be a linguist, I decided to get my MA in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL).

§§§

I knew I wanted to teach college, but back then just about every ad for a higher ed ESL instructor that I saw asked, in addition to the degree I’d just earned, for a year’s experience teaching abroad. Those programs wanted their faculty to have experienced at least a little bit of what it’s like to live in a country where you don’t speak the language, which I still think is a worthwhile requirement for someone who wants to teach ESL. Anyway, that’s how I ended up at the English Training Center in Seoul, South Korea. I actually applied for positions in a host of other places around the world, but I landed the job I did—in Yeoksam-dong, right outside the subway station—because I answered an ad in *The New York Times* placed by the aunt of the guy who ran the school. She worked at the Museum of Natural History and I remember that she interviewed me in her office. At the time, I knew nothing about Korea except that there had been a war there, that the United States had army bases in South Korea, and that the hit TV show M\*A\*S*H was a satire that used the Korean War to make statements about the insanity of war in general.

§§§

After I finished my MA, before I went to Korea, I taught advanced ESL composition as an adjunct at a four year college not far from where I lived. One of my most vivid memories from what time is of one of my colleagues coming to me with the paper of a student whose writing, in her view, was so removed from anything resembling reality that the only possible explanation was that the student was psychotic. (She was, I have to stress, not being ironic in the least. She truly believed the student must have been having a psychotic break when he wrote the essay.) She gave me the paper to read more as a curiosity than anything else, but I realized as soon as I started reading that the features of the paper that my colleague thought represented a break with reality were in fact quite common errors committed by speakers of Vietnamese when they first began to write in English. Clearly, the student has been misplaced into a regular composition class. I don’t remember what happened when I tried to explain this to my colleague, but it was certainly not my last encounter with the kinds of biases English Department faculty could bring to ESL writing.

§§§

Nassau Community College, where I teach now, hired me soon after I came back from Korea. One of the first positions I held within my department was as ESL Placement Coordinator. Simply put, my charge was to make sure that ESL students were placed in classes appropriate to their level of writing competence and to make decisions when a student was misplaced about which class to move them to. Once, a faculty member came to me with two diagnostic essays by students he said clearly did not belong in his class. I remember very clearly what he said. “They’re Spanish speakers, you know, and you know the kinds of errors Spanish speakers make: leaving off past tense verb ending, reversing adjective-noun word order, screwing up subject-verb agreement. In my class, they’ll never pass.” I took the papers from him, but when I read them, I discovered that one of these “Spanish speakers” was in fact from Jamaica. It actually said so in her essay. The other “Spanish speaker” turned out to be from Haiti, and her essay, which was almost letter-perfect, contained a single grammatical error. She’d misused the perfect infinitive continuous. (“To have been eating,” for example.) I would like to think that things are different now—and, to be fair, I think they are better—but I still hear stories from ESL students about how professors mistreat them because they are not natively fluent in English.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

.

Doors tae Naewye, by Christie Williamson: Written primarily in Shetlandic, a dialect of Scots that is spoken in Shetland, an archipelago off Scotland’s north coast, this is Williamson’s second book. (The first is Oo an Feddirs, which also contains a fair number of poems in Shetlandic.) Each Shetlandic poem is accompanied by a translation, printed in smaller, italicized text with slashes and double slashes to indicate line and stanza breaks. I wish the publisher had been able to print the translations on facing pages, though, because they are beautiful in their own right and being able to read them typeset as poems would help to give the reader a better sense of the syntactic, rhythmic, and sonic movements in the original. Williamson uses line breaks to great effect in this regard, for example, and the music he achieves melds the personal and the political into poems that, as often as not, command several readings. I met Christie Williamson before the pandemic shutdown, when he came to the States to be part of the annual poetry dinner held at the now defunct Roger Smith Hotel. I also brought him out to Nassau Community College, where I teach, to give a reading for our Creative Writing Program. We exchanged books afterwards, but I did not get a copy of Doors tae Naewye until my wife and I made a trip to Scotland over the summer and I was lucky enough to get to see Christie while were in Glasgow, before we made out way down to London for a family wedding. I was happy and more than a little bit humbled to find the title of my book incorporated into the first poem in this one:

Dawn

In LaGuardia I read

The Silence Of Men.

My case is checked,

devices safe and close

to hand. I wait.

I see a guy—be could be anything

from forty to seventy-five. Dreads

hang loose around his neck.

This guy has lived.

I see the torn rags

that just keep his feet off the ground,

taking step after step, always

forward—to what?

I think of the heavy shoes

I paid those bastards at American

to carry. I want to dig them out, say

“Here you go buddy—walk a mile.”

Like all these dreams it slips

away as quickly as it came.

I sit, with ten kilos of books

and not one word to say.

§§§

Octopuses are now punching fish in the face. This video shows exactly why. by Beki Hooper:

Individuals in the group do not share what they kill, but each group member increases the likelihood of making a kill by working together. Teamwork is therefore beneficial for everyone. That is, until individuals try to exploit the group by catching prey without helping to find it or flush it. The octopuses do not put up with this behaviour, though. They punish the cheaters by punching them with their tentacles.

Hooper reports on a study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution of underwater multi-species hunting groups in which Octopus cyanea, a species that is normally solitary, works with different kinds of fish to find prey. The roles within the group are pretty well defined. The fish decide in which direction the group should search for prey, while the octopus flushes the prey out of its hiding spot, but when “individuals try to exploit the group by catching prey without helping to find it or flush it,” the octopus assume the role of enforcer and punches the offending member. There are two videos in the article, one of an octopus punching misbehaving fish and one of the octopus and the fish hunting together. It’s in some ways a scientific version of the videos you see on social media of different species of animals befriending and cooperating with each other, but, as Hooper points out, the study raises some really interesting questions, among them the nature of octopus social intelligence and how the members of the hunting party communicate with each other, which scientists theorize might have to do with “octopus skin patterns.”

§§§

Black Hole, by Robert Jensen:

Some years are a complete blank, others are fragmented and sketchy at best. I have, literally, no recollection of the first six years of my life. From age six to eleven, it’s a jumble of disconnected fragments. Starting at twelve, I can start to accumulate enough fragments to piece together a tentative narrative, albeit with big gaps. And there’s one really big gap when I was fifteen, my sophomore year in high school; that year is completely blank. Starting with the year I was sixteen, I have something that seems to approximate the kind of memory most people taken for granted.

Jensen, whose work is worth checking out, perhaps especially his feminist writing, takes on in this essay—a guest post on Julie Bindel’s Substack—the way in which the abuse he suffered as a child has impacted his memory. For me, the most poignant part is when he considers whether it is better to know or not the things that he has blocked from memory and how comparing what it means not to know/remember to the situations of people who do know/remember can lead to some pretty counterintuitive feelings.

§§§

She Exposed a Prestigious Medical Journal’s Silence on the Holocaust. Now She’s Asking About Gaza, by Jonah Valdez:

“Is the silence of [The New England Journal Of Medicine] regarding the pulverization of the health care system in Gaza, and Israel’s relentless attack on health care workers and the creation of a public health and humanitarian disaster and the weaponization of starvation similar or different to its silence during the Holocaust?” Abi-Rached said toward the end of her talk, joining the symposium virtually from Paris. “What explains the erasure of the predicament of Palestinians in the pages of the journal? What do we mean by the political determinants of health if we precisely ignore the plight, the health, and well-being of marginalized and vulnerable populations?”

Comparisons of Israel’s war in Gaza to the Holocaust are often facile or straightforwardly (and even antisemtically) manipulative, not because what Israel is doing is not genocidal, but because singling out the Nazi’s campaign against the Jews as the point of comparison, when there are other genocides which would serve equally well, implicates all Jews worldwide in a collective responsibility and accountability for what the Israeli government is doing. The comparison Jonah Valdez reports on here, however, is well worth thinking about, since it is ultimately about institutional response to genocide—in this case on the part one of the longest-running and most prestigious medical publications in the country—regardless of who the perpetrators and victims happen to be. Joelle M. Abi-Rached and Allan M. Brandt published an article called “Nazism and the Journal” in the March 2024 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine.” Part of “an invited series by independent historians, focused on biases and injustice that the Journal has historically helped to perpetuate,” Abi-Rached and Brandt’s piece focused on the Journal’s choice to remain silent about the role played by the Nazi health care system in furthering the Nazi’s genocidal program. The authors were invited to speak about their findings at a symposium last week, and it was during that symposium that Abi-Rached asked the questions I quoted above.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

All images are from the National Gallery of Art and are in the public domain.

§§§

Rogier van der Weyden, Netherlandish, 1399/1400 - 1464

§§§

Rhodes & Carter (artist) American, 1890s - 1910s

§§§

William J. Rensler (artist) American, 1891 - 1946

§§§

§§§

§§§