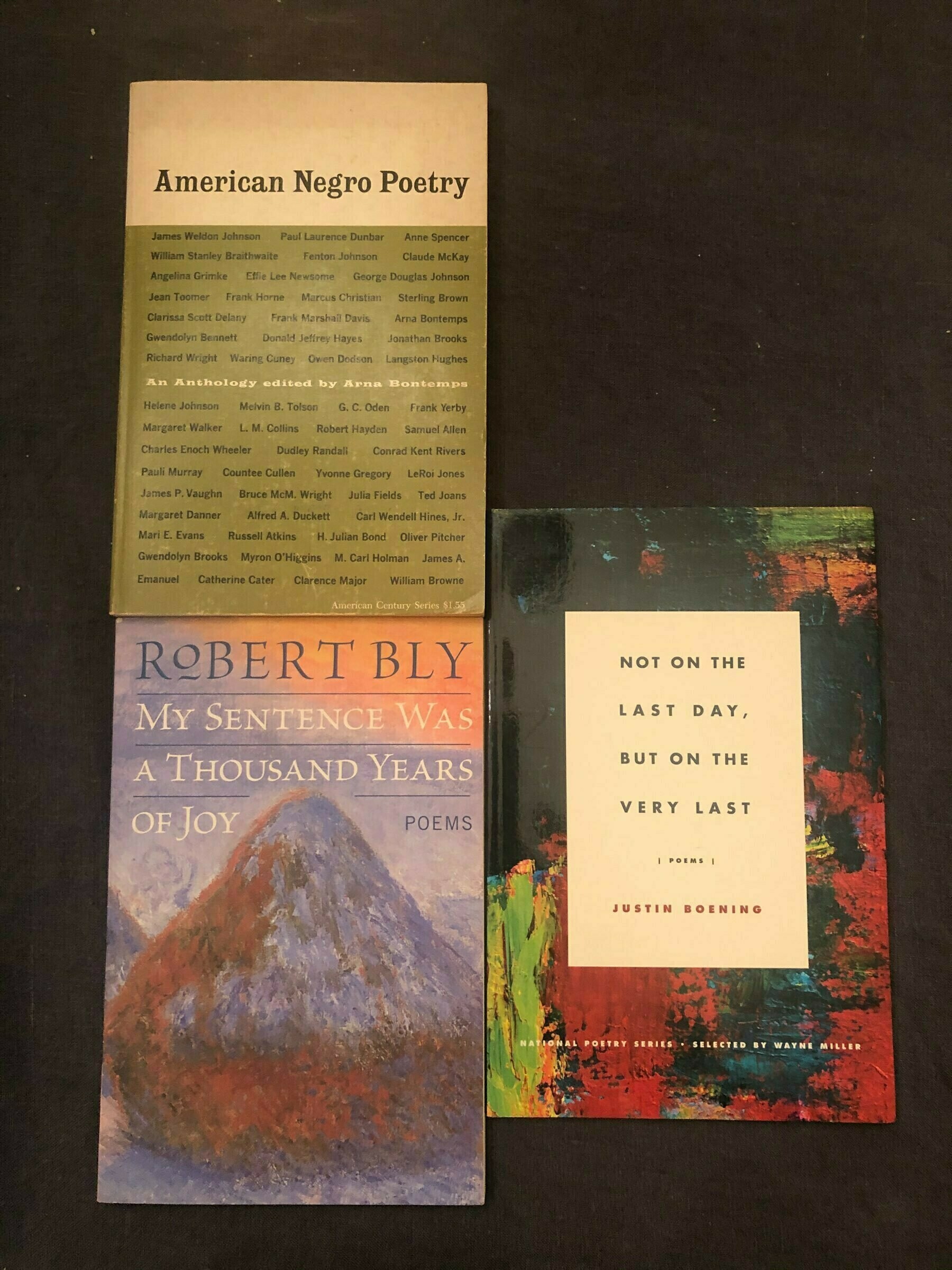

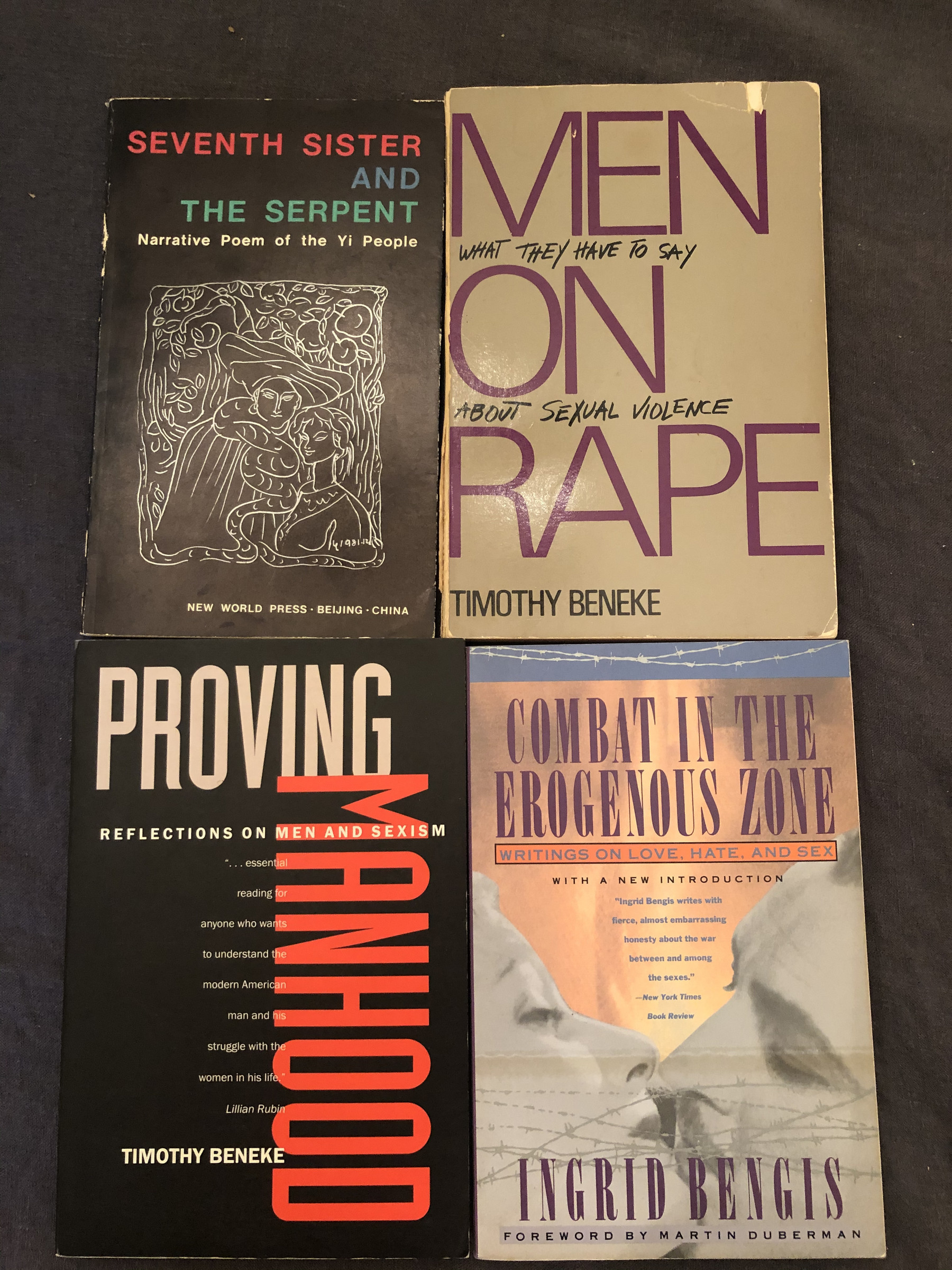

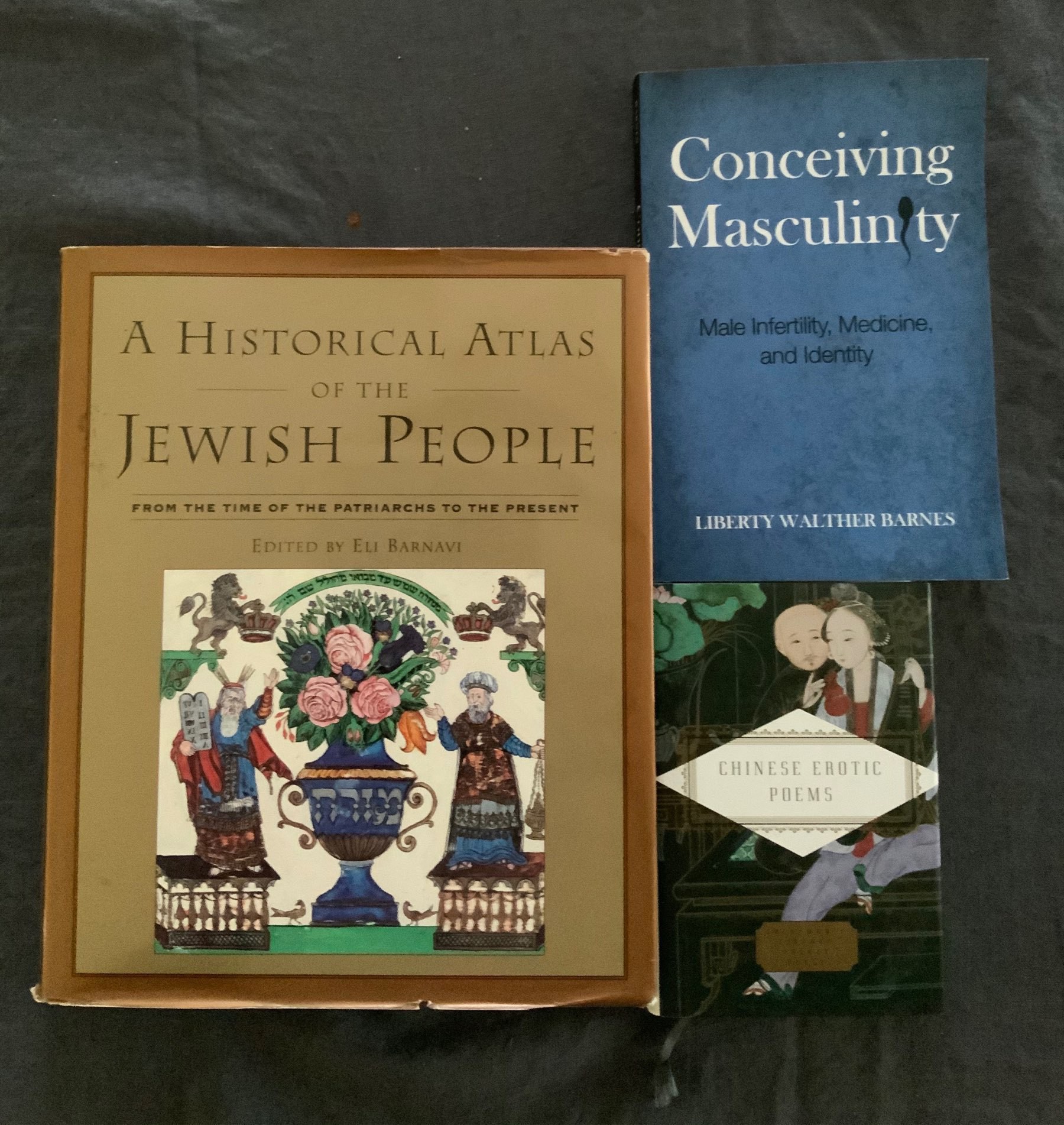

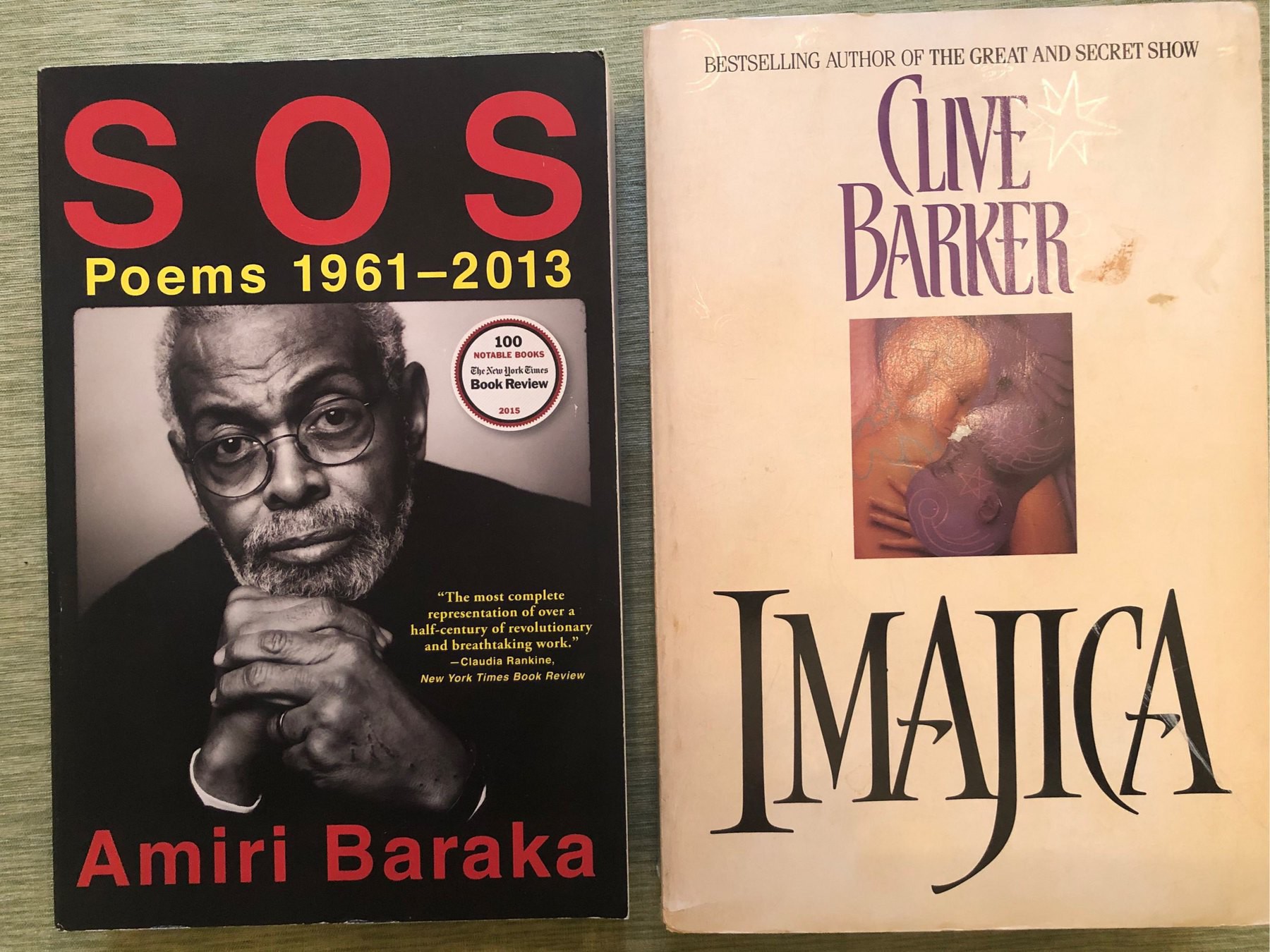

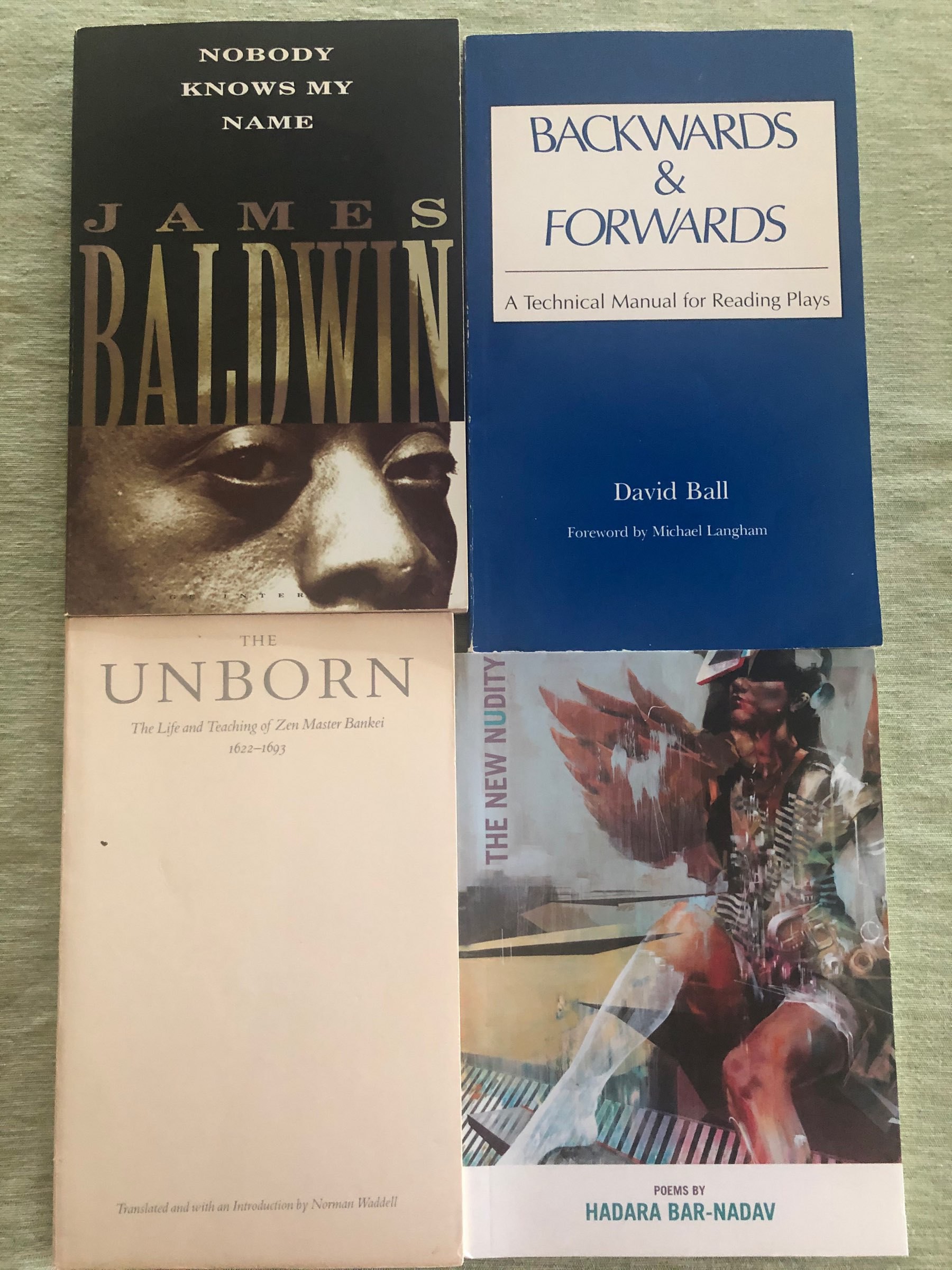

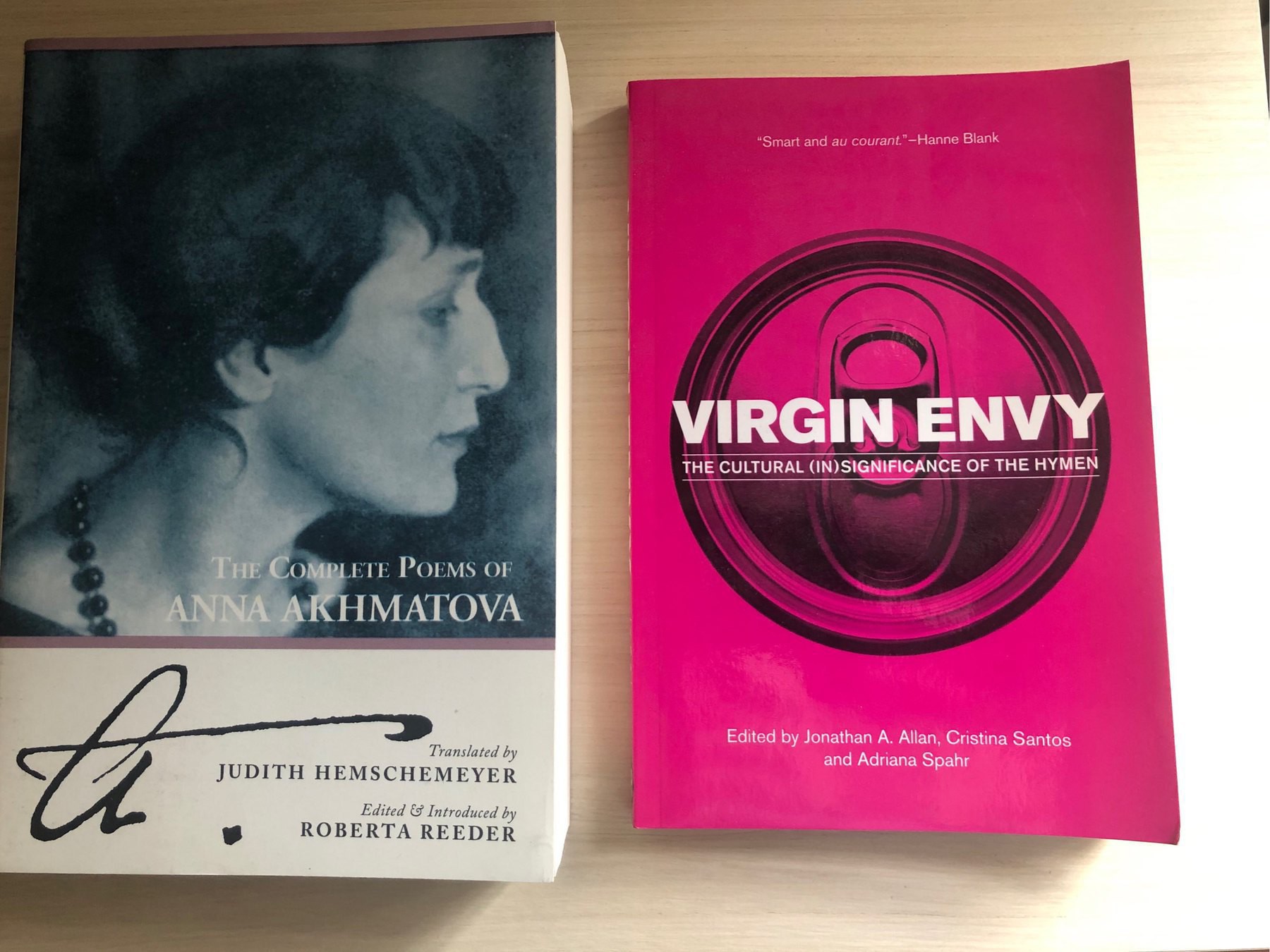

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #11

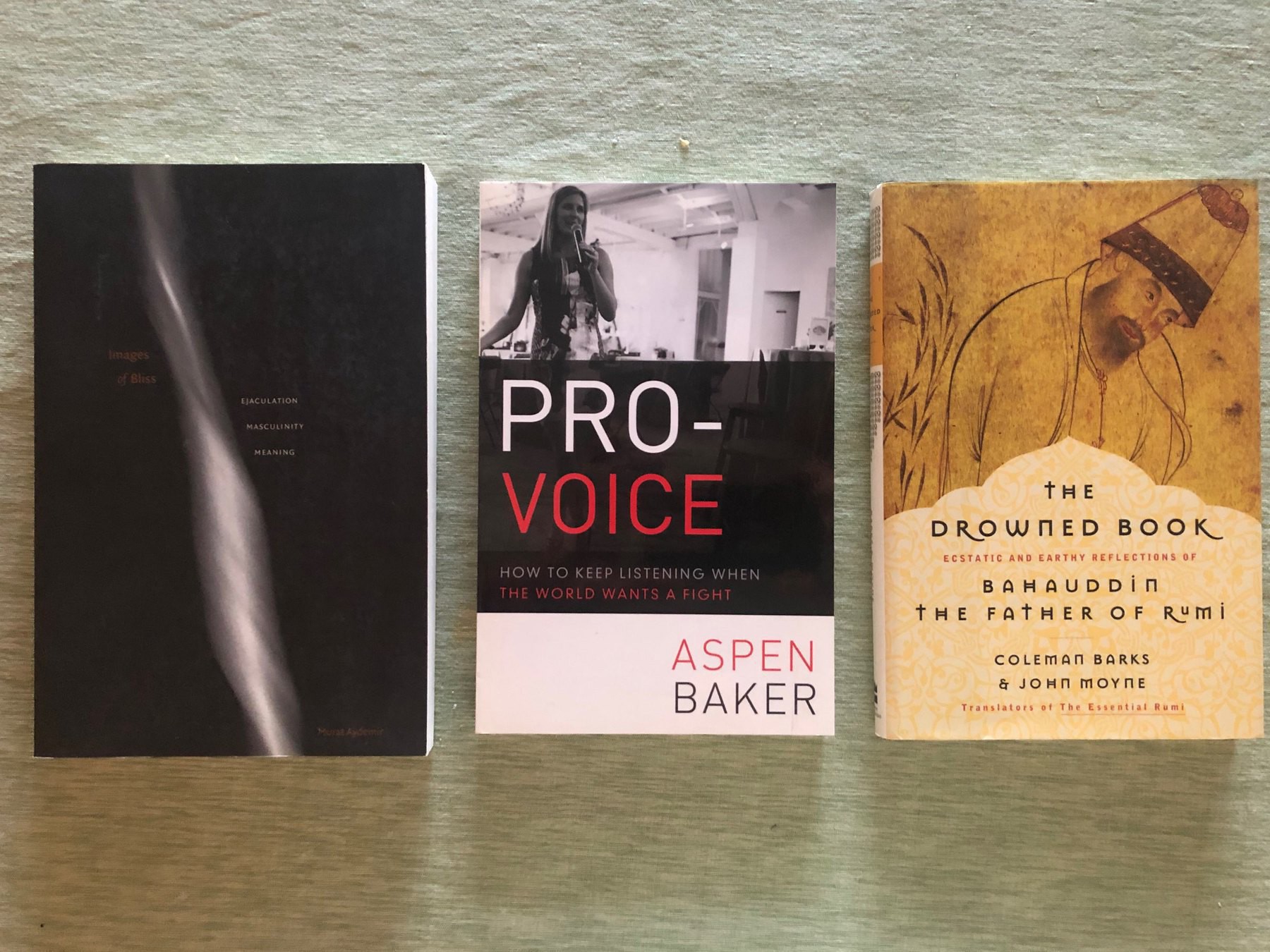

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #11

Because I can never read just one book at a time.

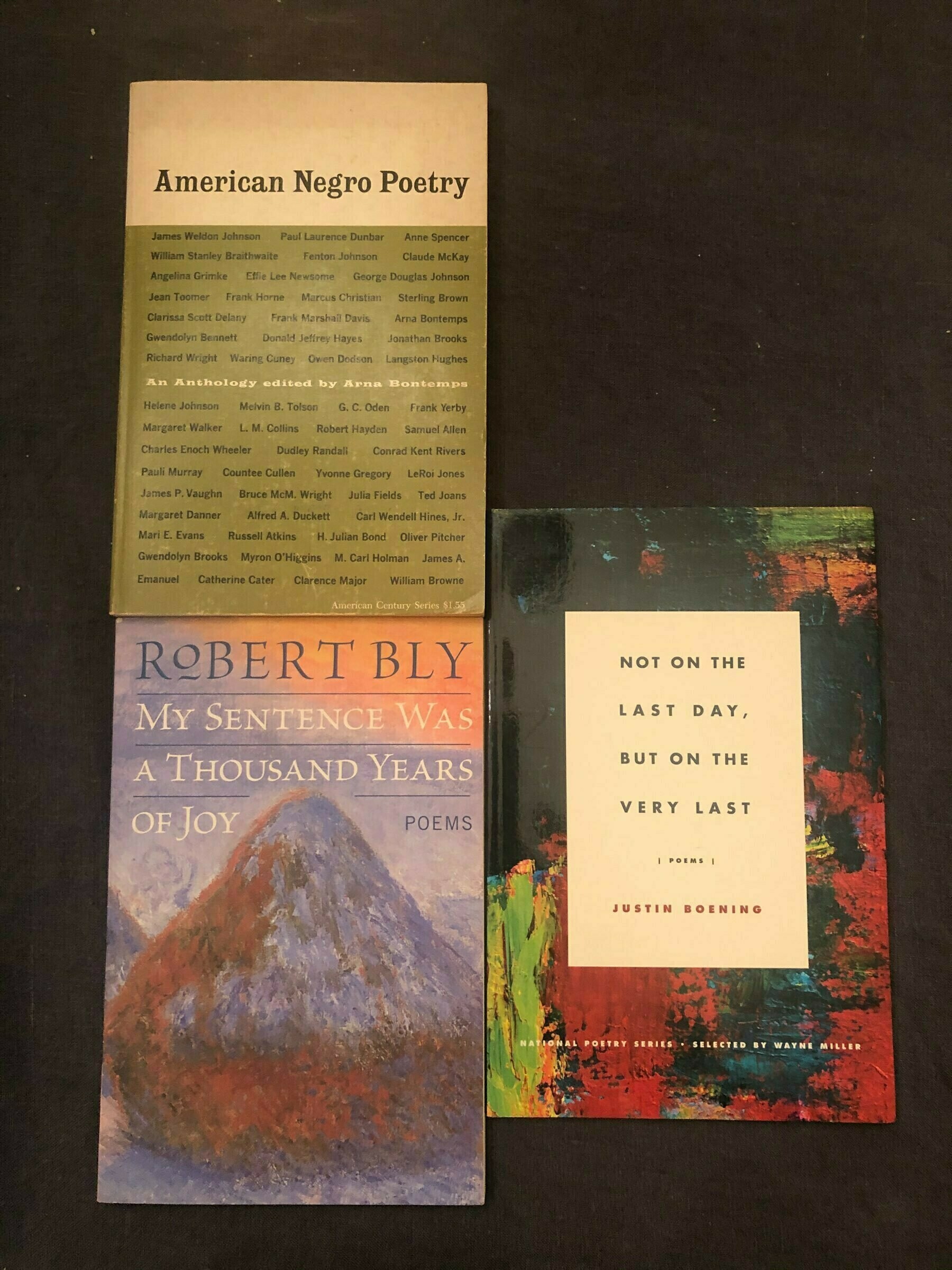

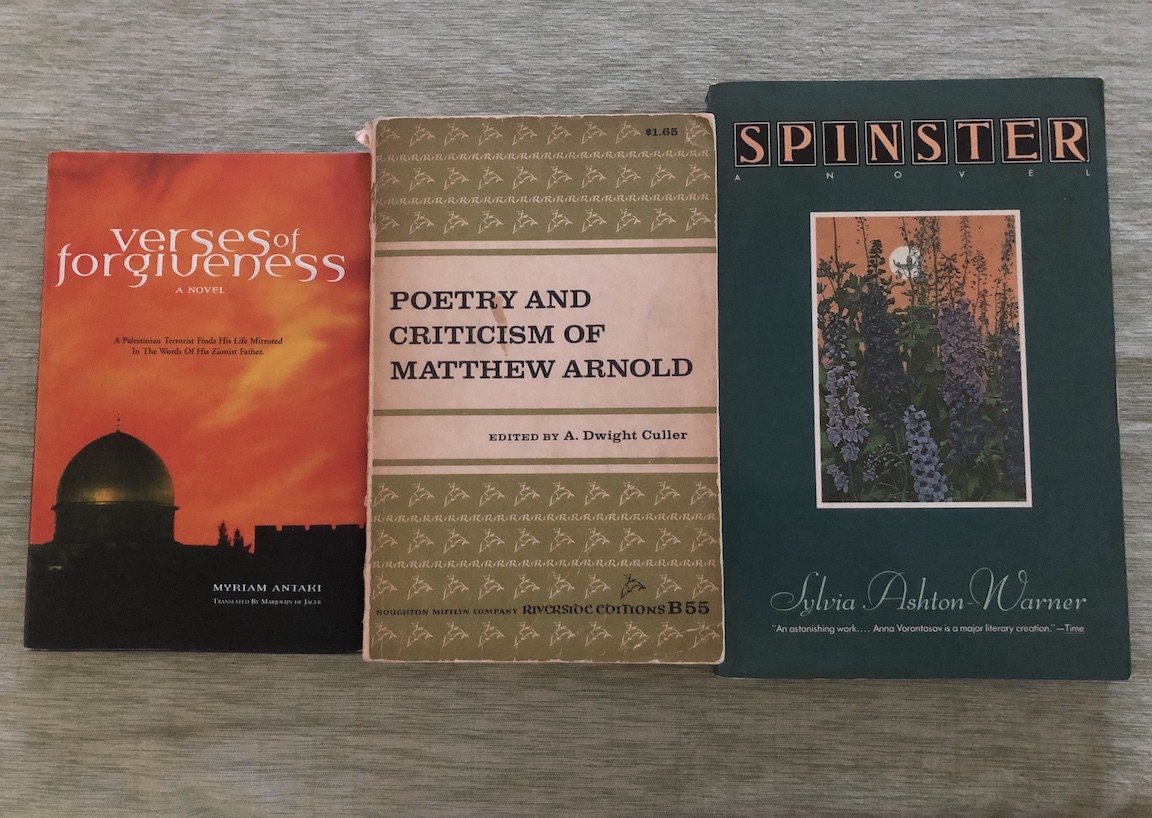

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #10

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #9

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #8

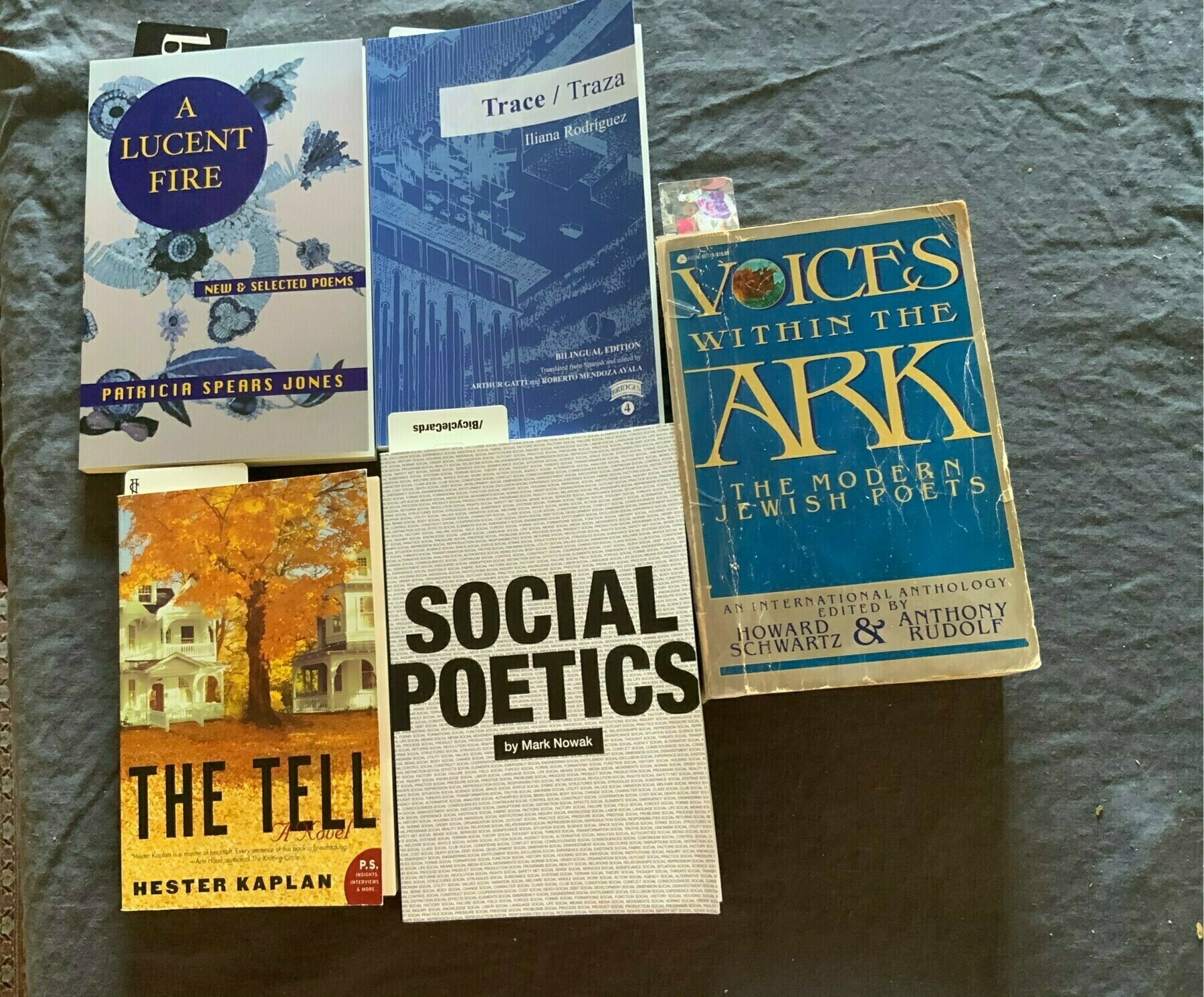

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #7

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #6

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #5

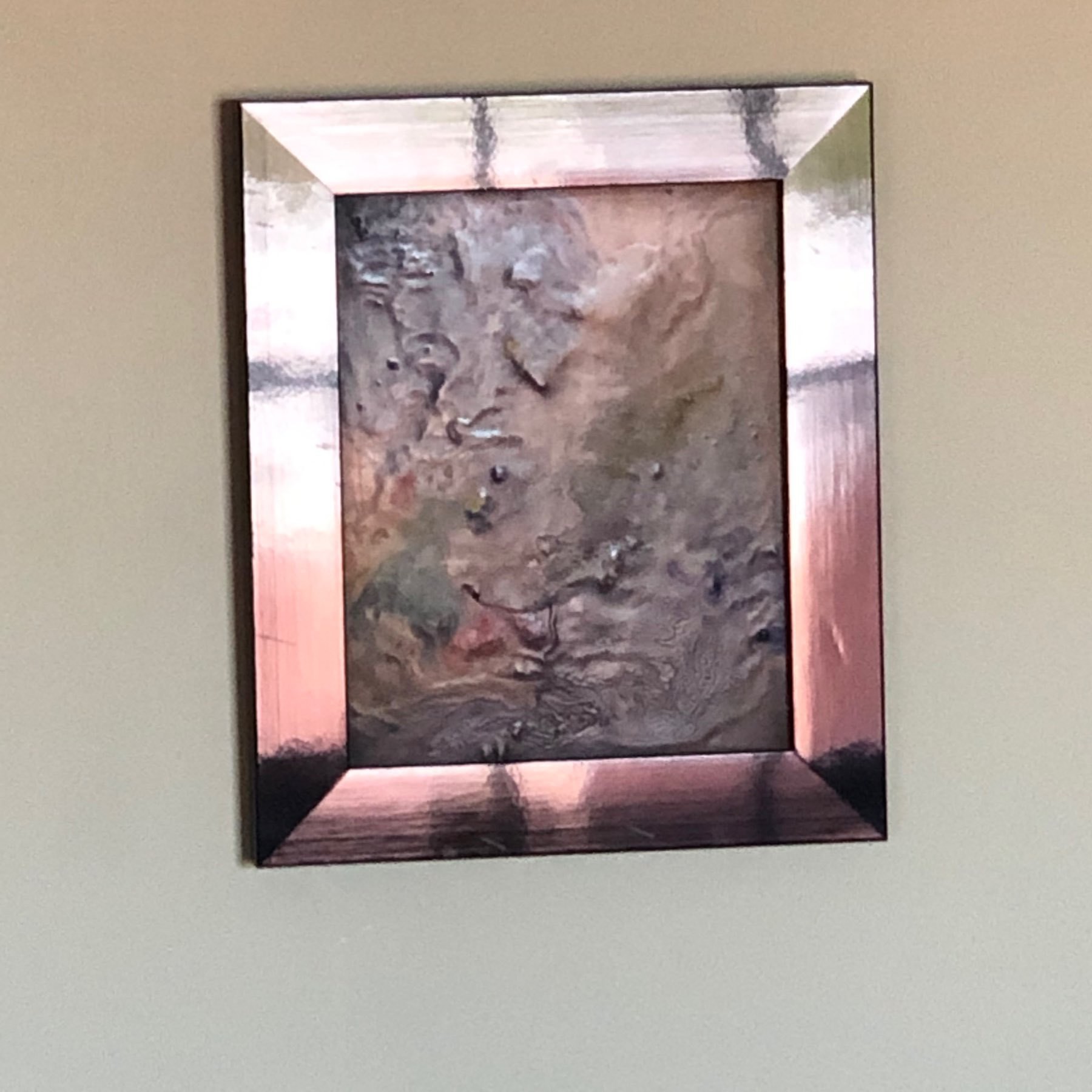

The same painting from two different angles.

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #4

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #3

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #2

Bookshelf Juxtapositions #1

Sunday morning, reading a first book by someone I know casually, who is really crappy at writing dialogue. I’m interested in the story, but there’s so much unconvincing and often cliché back and forth between the main character and his best friend…and I’m only up to chapter 3.

I’m thinking today about contract negotiations, the shrinking budget for public higher education in NYC, how the pandemic has exacerbated that, and what if the executive committee I serve on turns out to be the one on whose watch the campus where I teach starts laying people off?

My Year-Long Writing Project - first post on my new Blot website.

Even Layla thinks it gets boring. She won’t even look at the papers.

One of the hardest parts of paper grading for me is the monotony. My students—who’re the same age as always while I’m older—are of course thinking these thoughts for the first time. I, on the other hand, have been reading them, or thoughts very close to them, for many semesters.

This poem, by Ellen Bass, is lovely and painful and necessary:

“I want your scent in my hair.

I want your jokes.

Hang your kisses on all my branches, please.

Sink your fingers into the darkness of my fur.”

Grading, grading, without an end in sight…

(To the tune of “sailing, sailing…)

The latest issue of my newsletter is out, focused on the process of putting together a book of poems and the new website I’ve put together (on Blot) for the reading series I run.

It’s interesting, sadly predictable, and not a little disturbing, that it was a picture of two young Muslim women wearing hejabs that sparked the most controversy.

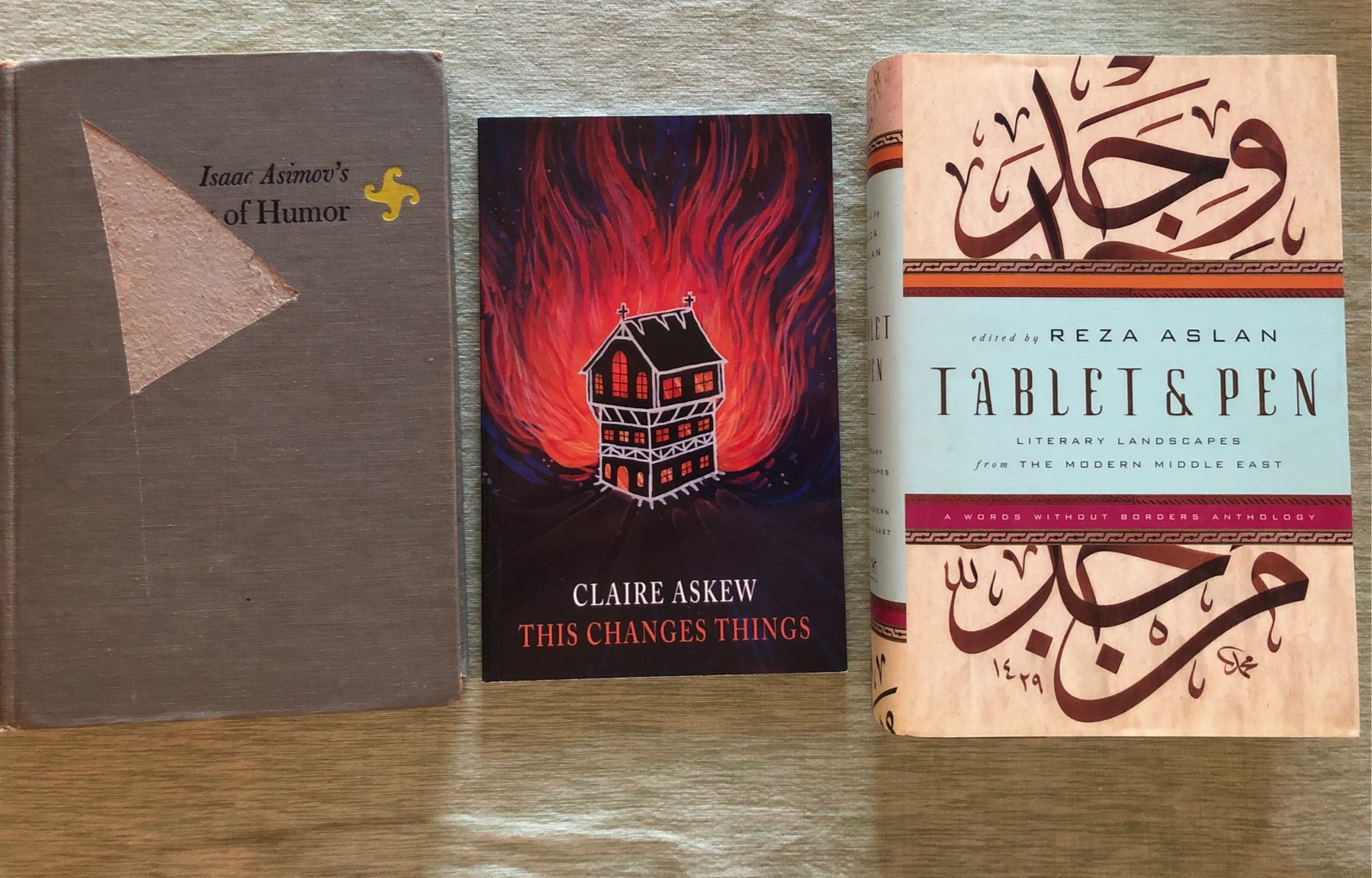

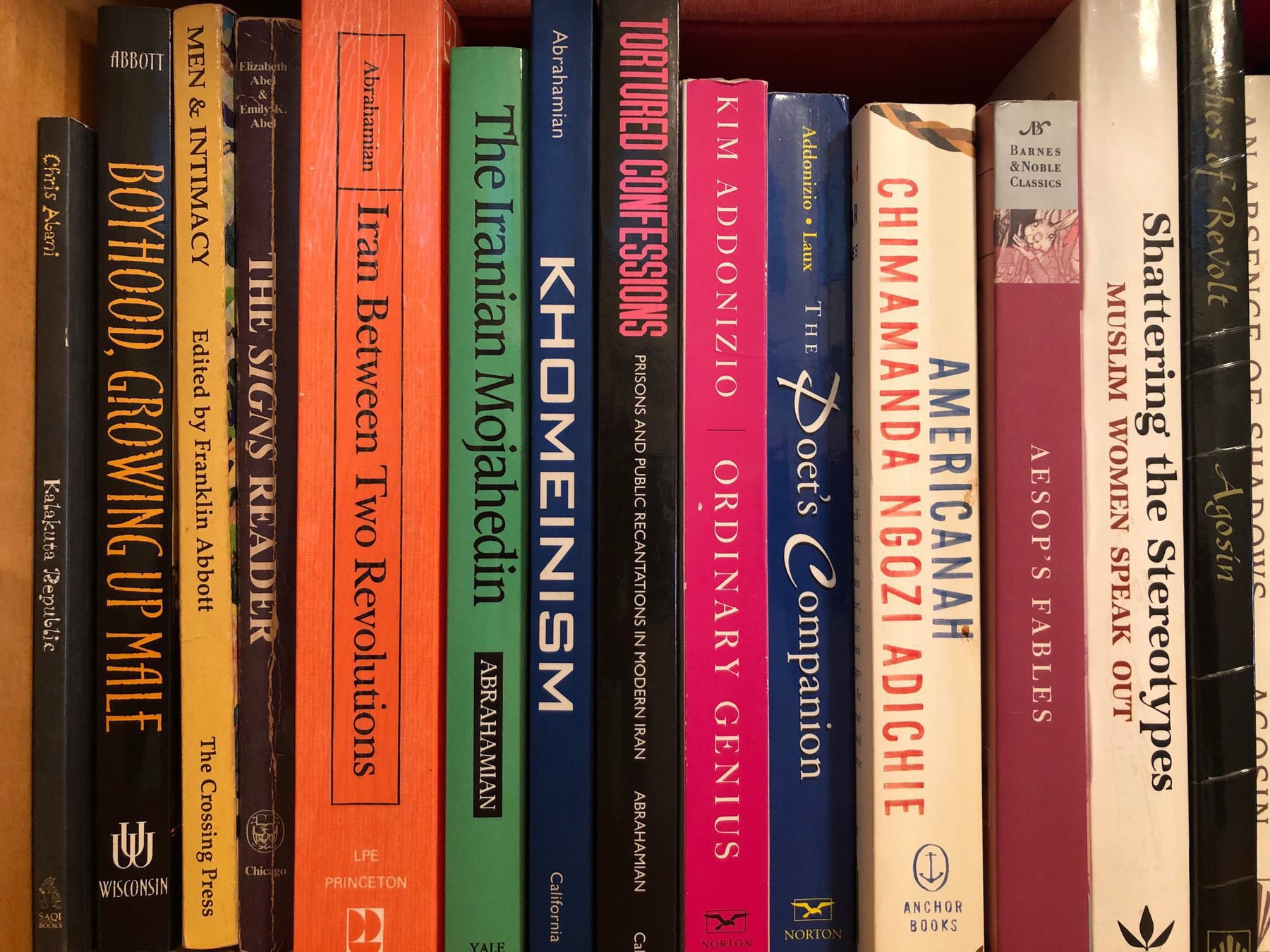

The unread results of my resolution not to acquire too many new books over the last two years. To be fair, I was given, or won in random drawings, and so did not buy, most of them. Still…

A day or so ago, in response to the escalating tensions between Iran and the United States, I posted to Twitter my version of what are perhaps the most famous lines written in 13th Iran by Sa’di of Shiraz:

From Sa'di of Shiraz (13th century Iran), 1 of 2:

— Richard J Newman (@richardjnewman) January 5, 2020

"All men and women are to each other

the limbs of a single body, each of us drawn

from life’s shimmering essence, God’s perfect pearl;

and when this life we share wounds one of us,

all share the hurt as if it were our own..."

The last two lines of the verse, in case you don’t want to click through to see the second tweet in the thread, are:

You, who will not feel another’s pain,

no longer deserve to be called human.

Oonagh Montague replied with this important question:

Although how do we translate those words to a world where, in order to preserve sanity and be able to keep going, we advocate not listening to the constant bubble of wars and pain from a million media channels?

— Oonagh Montague (@MontagueOonagh) January 7, 2020

She made me think that it would be good to post the entire piece from which those lines are taken. It’s from Sa’di’s Golestan–the title means Rose Garden—which is a collection, broadly speaking, of teaching stories that combine prose and poetry. Notable about the story the lines I tweeted come from, which is in “Kings,” the first section of the book, titled “Kings,” is that they are specifically directed at a despotic ruler who as asked for the help of Sa’di’s speaker. In other words, they are not intended as an abstract expression of liberal humanism, but, rather, as practical advice for how the ruler can achieve the ends he desires. Here is the story in its entirety, which I think speaks for itself in all kind of ways:

An Arab king who was notorious for his cruelty came on a pilgrimage to the cathedral mosque of Damascus, where I had immersed myself in prayer at the head of the prophet Yahia’s [John the Baptist’s] tomb. The king prayed with deep fervor, clearly seeking God’s assistance in a matter of some urgency:

The dervish, poor, owning nothing, the man

whose money buys him anything he wants,

here, on this floor, enslaved, we are equals.

Nonetheless, the man who has the most

comes before You bearing the greater need.

When he was done praying, the monarch turned to me, “I know that God favors you dervishes because you are passionate in your worship and honest in the way you live your lives. I fear a powerful enemy, but if you add your prayers to mine, I am sure that God will protect me for your sake.”

“Have mercy on the weak among your own people,” I replied, “and no one will be able to defeat you.”

To break each of a poor man’s ten fingers

just because you have the strength offends God.

Show compassion to those who fall before you,

and others will extend their hands when you are down.

The man who plants bad seed hallucinates

if he expects sweet fruit at harvest time.

Take the cotton from your ears! Your people

deserve justice. Otherwise, justice will find you.

All men and women are to each other

the limbs of a single body, each of us drawn

from life’s shimmering essence, God’s perfect pearl;

and when this life we share wounds one of us,

all share the hurt as if it were our own.

You, who will not feel another’s pain,

no longer deserve to be called human.