Four By Four #27

Writing News

A poem of mine, “Sunset,” was just published in Humana Obscura, a lovely literary journal that I recommend to you all.

Four Things To Read

I Was Wrong About Trigger Warnings, by Jill Filipovic: “Most of the experts I spoke with were careful to distinguish between an individual student asking a professor for a specific accommodation to help them manage a past trauma, and a cultural inclination to avoid challenging or upsetting situations entirely.” As a teacher, I have never liked trigger warnings, not because I think there is no merit in the idea that students deserve fair warning that they are going to be reading “difficult” or “problematic” texts, but because the warnings themselves have always seemed to me a sign of pedagogical laziness. Good teaching, it seems to me, calls for instructors to put that kind of material in context for students, providing them beforehand with a critical framework with which to approach the text, especially when it comes to the difficult or problematic aspects of the work in question. My own experience has been that students who might need an accommodation—up to and including the chance to read a different text—or even just a reassuring conversation about the one that has been assigned, are more likely to approach me if I provide that kind of framework than if I give one of the canned trigger warnings that have become so common. Filipovic’s essay doesn’t deal so much with what I have just described, but it’s a thoughtful consideration of this subject nonetheless, and worth reading. (I will also add that I think it’s similarly lazy pedagogically if the only texts one can assign that deal with what we might broadly label “trigger-warning-appropriate subjects” are those that center trauma and therefore primarily invite teaching strategies that do the same in the classroom.)

Aunt Taibele, by Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn, translated from Yiddish by Miranda Cooper: “She hated going to celebrations as much as she loved going to funerals. For her, going to a wedding or a bris was a punishment. At parties she would sit hidden in a corner and watch the happy family members with a sour expression; it got on her nerves to see young people merrymaking and beaming with joy, and she would sneak quietly out of the hall.” Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn (1905–1975) was born in Nowo-Radomsk (today Radomsko), Poland. Her work, according to Cooper’s introduction was “radical for its time: it is feminist simply in its implicit assertion of the literary value of women’s domestic and emotional lives.” It is worth mentioning that the end of the story incorporates a Jewish folk tradition we would today find deeply problematic: plague weddings, known as mageyfe khasenes or shvartse khasenes (literally black wedding. This superstitious ritual involved marrying people on the margins of society to one another in an effort to ward off the plague. I’d never heard of this tradition till I read this story, but a Google search revealed this article in Tablet, which gives a history of the custom.

The Blue Collar Jobs of Philip Glass, by Ted Gioia: “His family was opposed to his music career. They feared he would turn out like Uncle Harry, a dental school dropout who worked as a drummer in vaudeville and Borscht Belt hotels. So how did Glass pay his way at Juilliard? Glass, like the musicians mocked in the song ‘On Broadway,’ took a Greyhound bus back home to Baltimore. But he didn’t stay there for long—just five months. He made enough money in that time to pay for his New York education. But that’s only because this intrepid 20-year-old aspiring composer somehow convinced Bethlehem Steel to give him a job at their plant in Sparrows Point, Maryland.” What I resonate with most in this article is the respect Gioia expresses both for Glass’ commitment to his art and the humility that is embodied not just in the kind of work Glass did to support himself, but in the way he embraced that work as an equally, if differently, valuable part of who he was. I especially appreciated the story Gioia quotes from a 2001 interview Glass gave to The Guardian:

I had gone to install a dishwasher in a loft in SoHo. While working, I suddenly heard a noise and looked up to find Robert Hughes, the art critic of Time magazine, staring at me in disbelief. ‘But you’re Philip Glass! What are you doing here?’ It was obvious that I was installing his dishwasher and I told him I would soon be finished. ‘But you are an artist,’ he protested. I explained that I was an artist but that I was sometimes a plumber as well and that he should go away and let me finish.”

The Lost Art of Waiting, by Christine Rosen: “To be kept waiting is generally viewed as a negative experience; to make someone wait often denotes hierarchy, dominance, or power in a relationship.” Rosen troubles this notion by talking about how waiting can be a positive experience, using as examples people whose happiness, according to a Dutch study, was rooted in the pleasurable anticipation of a vacation they were planning, not in having taken the vacation in and of itself. She also makes some interesting connections between what she doesn’t quite call a culture of impatience with the ever-increasing speeds at which digital technology offers up its content. The article made me think of the Slow Food Movement.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

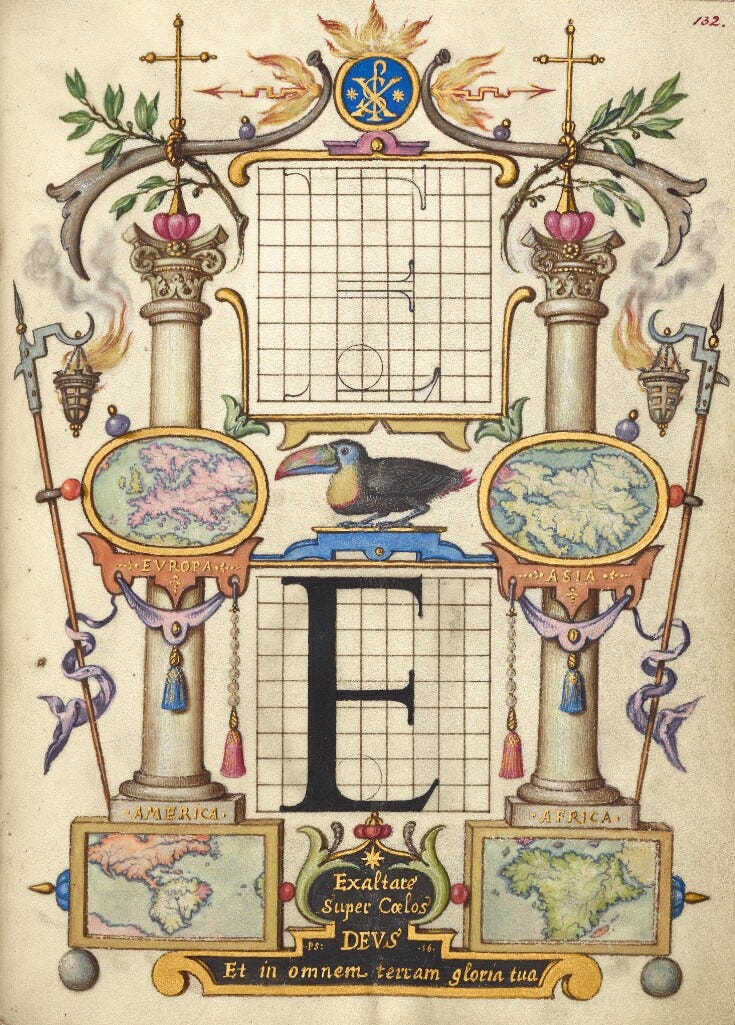

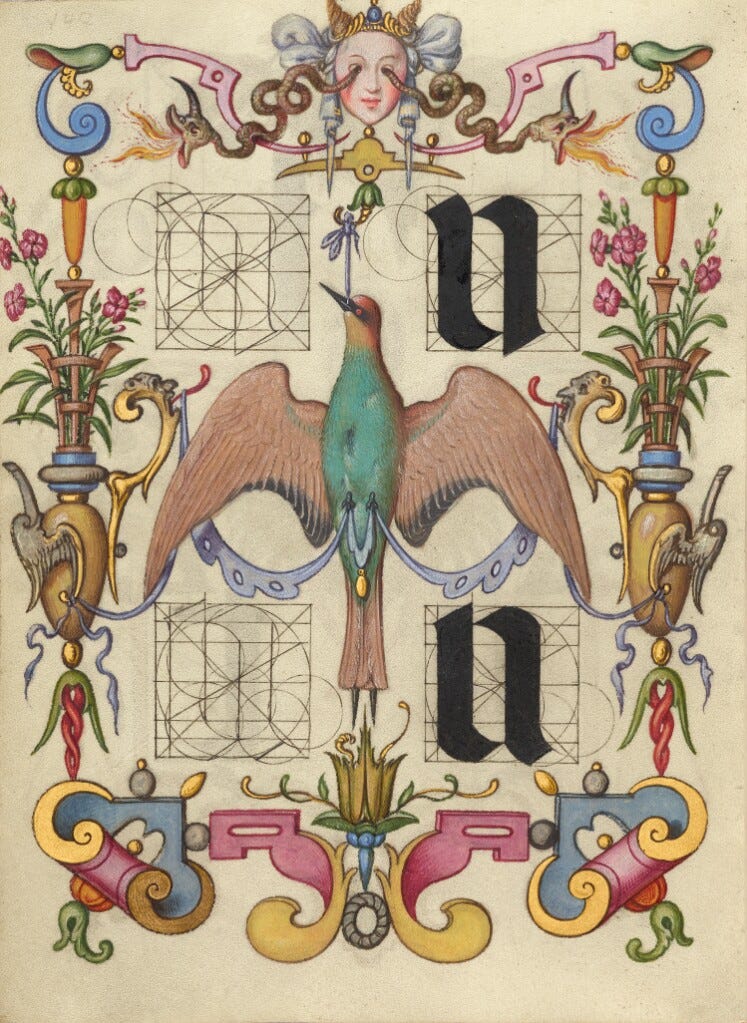

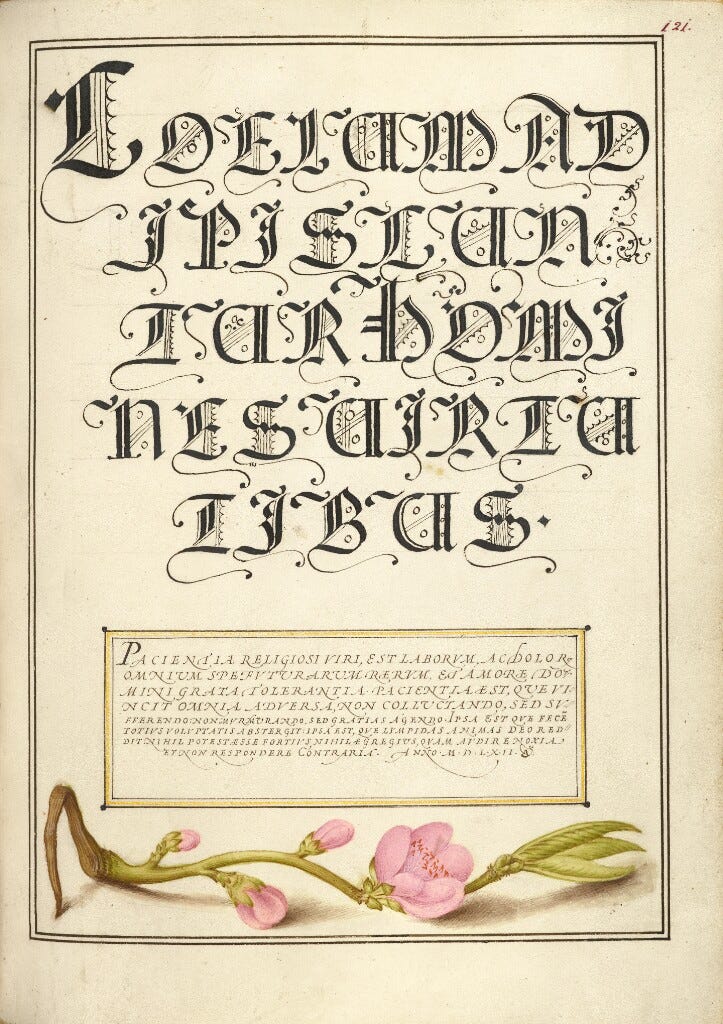

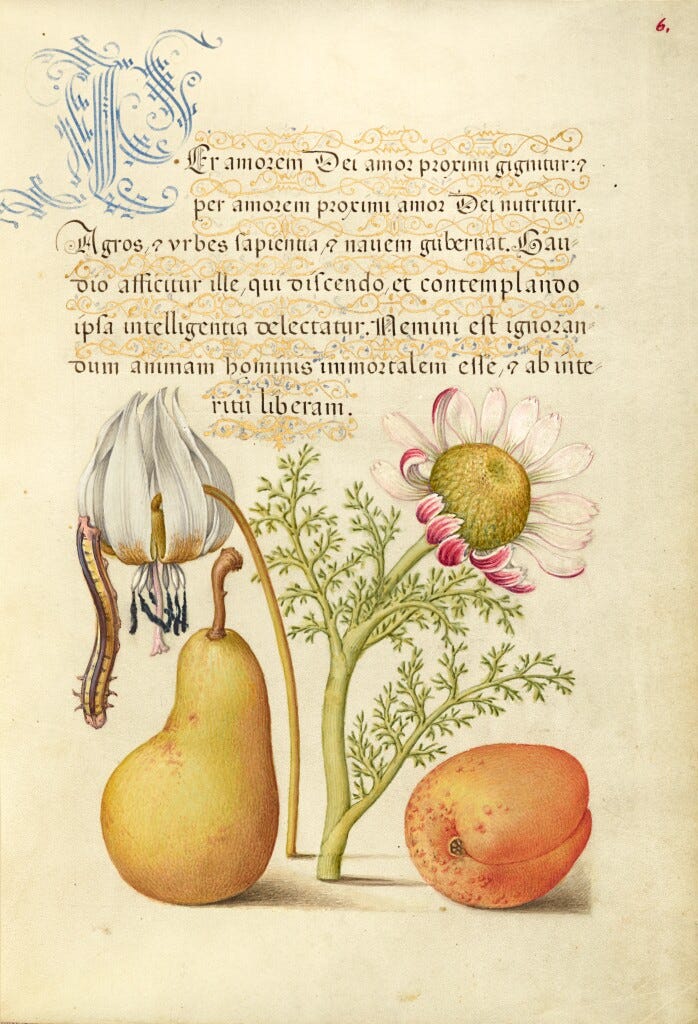

Four Things To See

These images are all from the Library of Congress and are in the public domain.

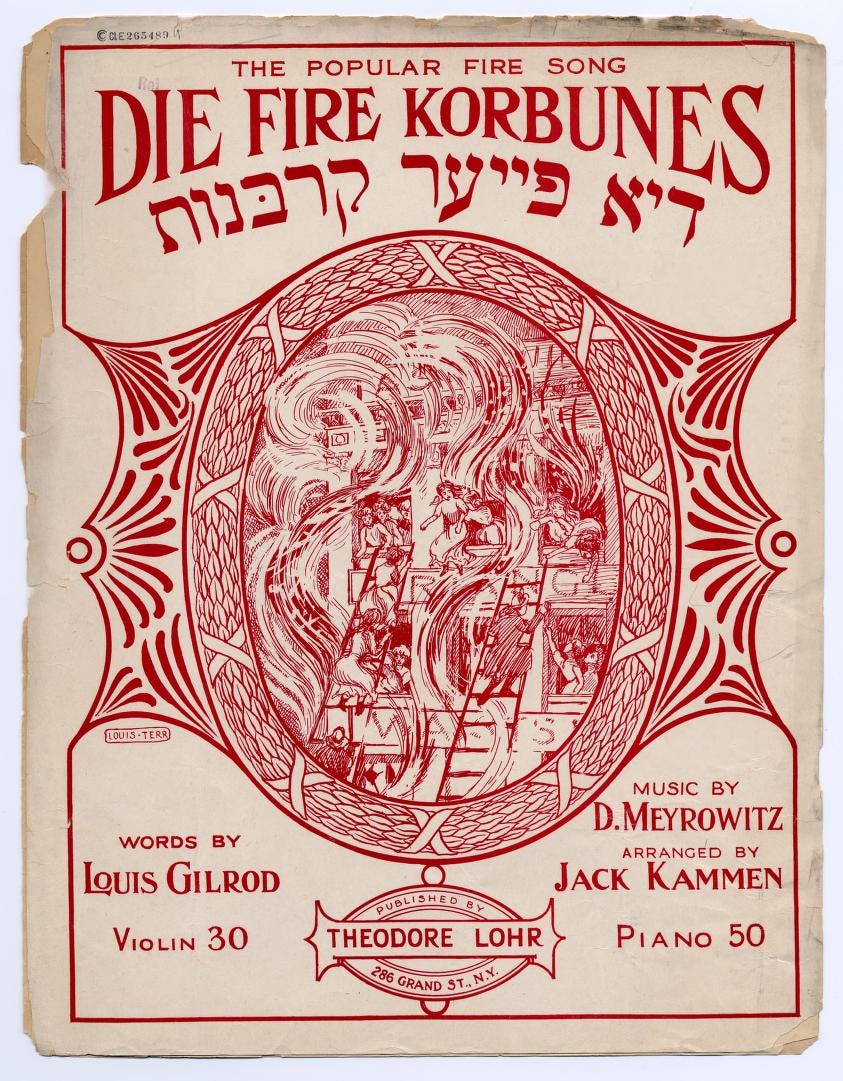

Sheet music cover for “The Popular Fire Song”

An elegy for the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Co. fire. (Source: Heskes, Irene, Yiddish American Popular Songs, 1895-1950)

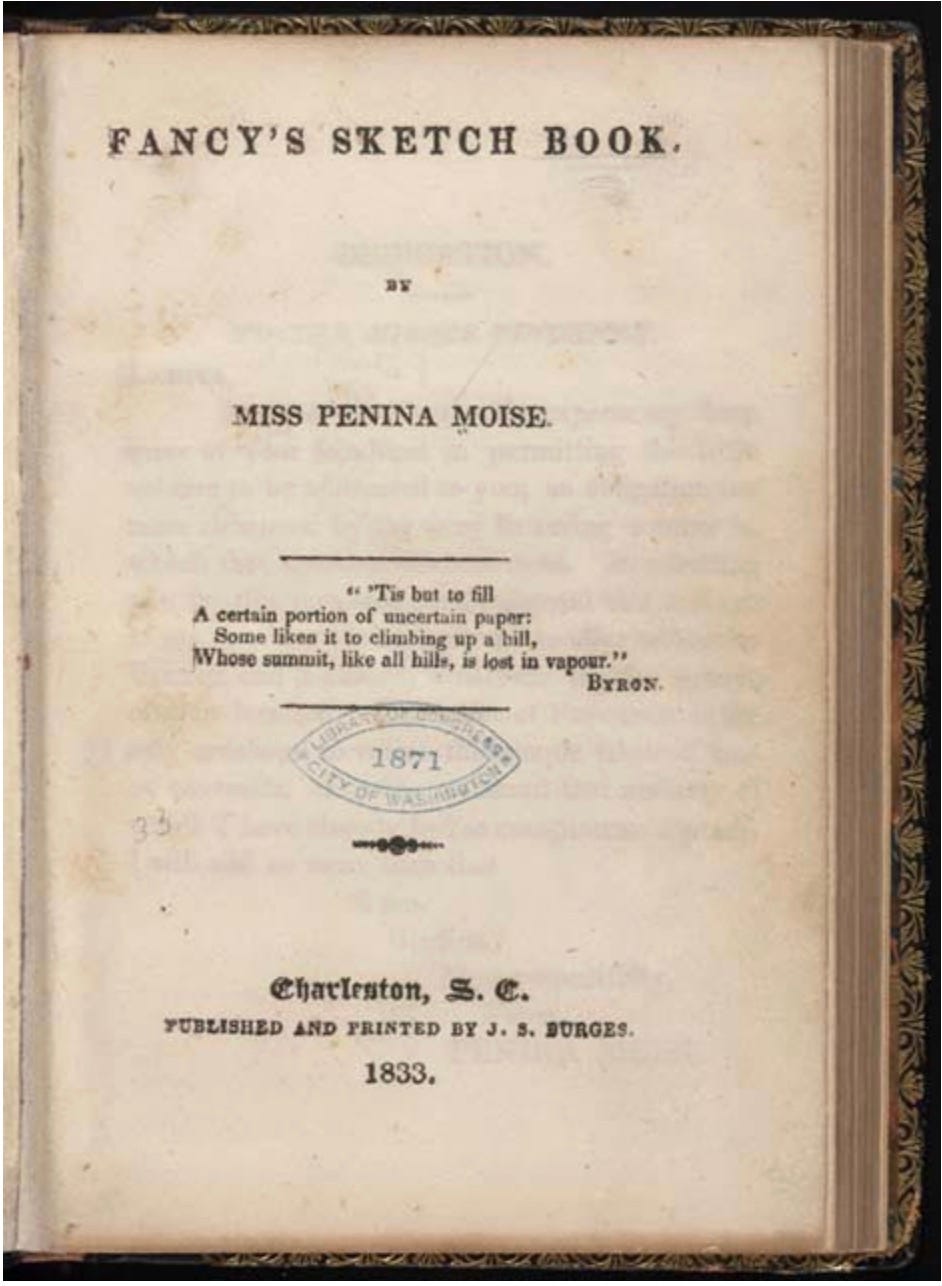

Cover of Fancy’s Sketchbook: First Published Work by an American Jewish Woman

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Penina Moise (1797-1880) became a widely published author and poet. A deeply religious woman, she composed hymns for use in prayer service as well as this book of poetry, which includes poems on biblical themes and on contemporary Jewish life. Few copies survive of Moise's collection of verse.

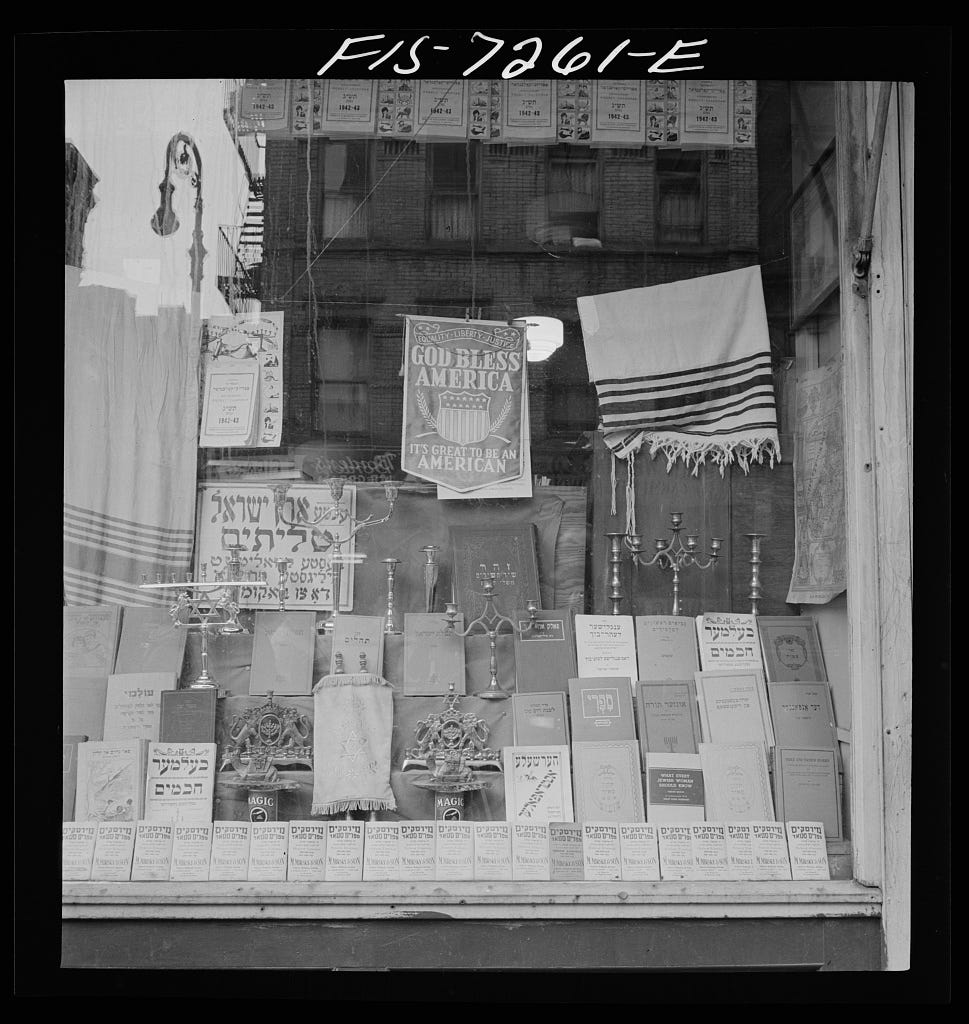

Window of a Jewish religious shop on Broom Street

Taken by the photographer Marjory Collins (1912-1985), probably in August 1942.

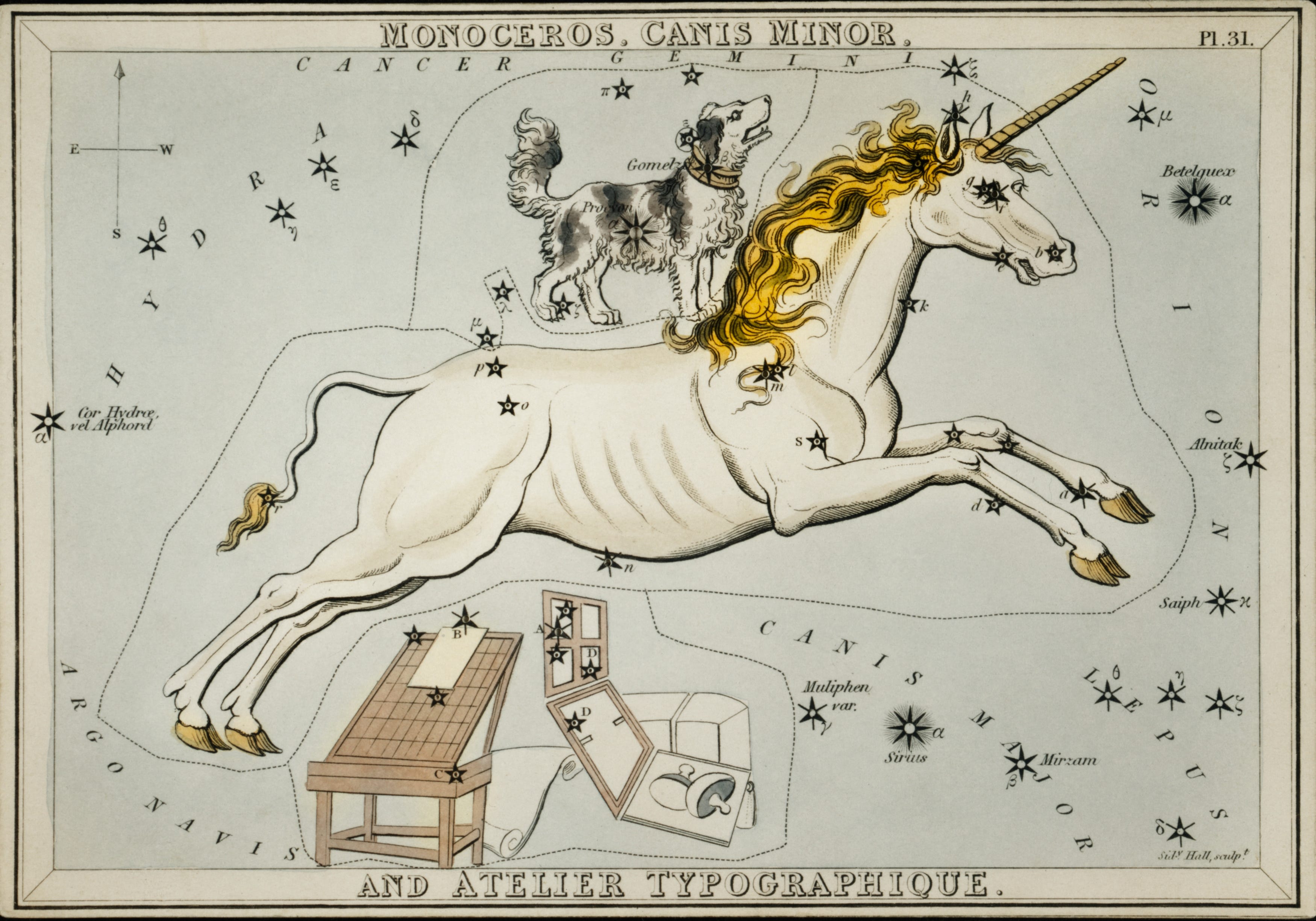

A Portrait of Two Girls Wearing Banners with Slogan “Abolish Child Slavery!!” in English and Yiddish

Probably taken during May 1, 1909 labor parade in New York City. Published in American women: a Library of Congress guide for the study of women's history and culture in the United States, edited by Sheridan Harvey [et al.]. Washington: Library of Congress, 2001, p. 347.

Four Things To Listen To

“5784” by Six13

This is just to say an early Shanah Tovah! to all who celebrate.

Yer Blue Hair, by Alfonso Vélez

If Something Breaks, by Front Country

Barton Hollow, by The Civil Wars

Four Things About Me

Recently, I was looking through some old photographs and I found a bunch from when my brother and I were little and we would spend big chunks of our summer at the place my grandparents had in upstate New York. I hadn’t thought for a long time about how we used to run around naked in the grass, sometimes taking rain showers, if the weather was warm and the rain gentle enough; sometimes splashing around in the kiddie pool we had; sometimes playing in the water from the sprinkler my grandmother used to water the lawn. I look at those pictures now and they seem so innocent. My brother and I were laughing together, having a good time, in the completely unselfconscious way children have of being in their bodies, whether clothed or naked. Then I think about how these pictures would be received if they were taken today. Would the person who took them, probably my mother, be reported as a possible child pornographer, the way Sally Mann was flagged for her very professional, very artistic pictures of her own children? Probably they would be; and if they were, what would it take for my mother to demonstrate she was not sexually exploiting her children. I am well aware of the dangers pedophiles pose, of just how ubiquitous child pornography is if you know where to look for it, of the damage sexual exploitation does to children. No one has to convince me of the need to be vigilant, but it makes me sad that someone now might look at these pictures that are more than fifty year old and find the act of having taken them in the first place to be a questionable act at best. To me, that means, for all our vigilance, we have lost something that was worth preserving.

I taught a couple of sections of freshman composition as a graduate TA when I was at Syracuse University. One time—and I know this sounds like something out of a movie satirizing the kind of story I am going to tell you, but it actually happened this way—a young woman sitting in the second row, almost directly in front of me, started blinking at me and pursing her lips. I did not notice at first, but once I did, it became very distracting, especially because, in my own naivety, I could not figure out why she was doing it. The fact that she might have been trying to flirt with me was the farthest thing from my mind. Eventually, though, it dawned on me that this was exactly what she was doing, and a range of emotions flooded through me. I was indignant, embarrassed, a little bit flattered, and profoundly uncertain about whether and how to respond. Finally, because I was finding it more and more difficult to ignore her and stay focused on whatever the lesson was, I looked straight at her and blurted out, “Are you blowing kisses at me?” She, of course, was mortified and, if I remember correctly, left the room and never came back to class. While it’s silly to wish for a do-over for something like this—which took place, after all, forty years ago—I do sometimes wonder what happened to that woman after she left the room. It feels odd to say now that I hope she was not seriously scarred by my insensitivity, but that is how I feel.

That year, we were forced to teach from a book called *The Practical Stylist,* by Sheridan Baker, which I hated, not the book per se, but the way we were expected to teach from it. It wasn’t that I thought I knew better than Baker about what good writing was, or about what it took to craft an argument, but I distrusted from the start the slavish way we were expected to adhere to the text in our classrooms. We were given little room for flexibility and experimentation in how we taught the material—at least if we wanted to get a good teaching evaluation and a passing grade from the professor, whose name I have forgotten, who supervised the TAs and taught our practicum. Even back then, before I really knew what I was talking about, I had the same doubts about teaching Baker’s five paragraph essay, including what he called “the concession paragraph,” that I had about the pass-fail, in class, five paragraph final essay exams ESL students have to take at my institution in order to move up a level in their classes: almost nowhere else in the world but an English Department will they ever have to write like that.

My brother’s name—he died in a car accident a very long time ago—was Paul. So, Paul Newman. I don’t remember how old we were when we discovered that he shared that name with a very famous movie star, but when we did, we decided to make some money by selling “Paul Newman’s” autograph for $.25 a piece. This was back when a quarter actually bought you a candy bar at the corner store. I have no memory of how many we actually sold, except that I know we sold some, nor do I remember which adult found us out, though I know someone did, or if we were forced to give the money back. I do wish, though, that I could recall the whole thing in more detail.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.